Non-avian dinosaur eggs took a long time to hatch — between 3 and 6 months, according to new research on the teeth of fossilized dinosaur embryos.

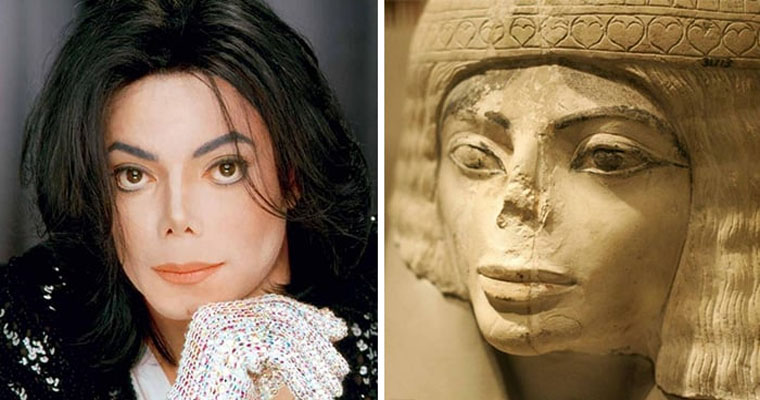

Herds of female titanosaurs gathered at traditional nesting grounds 80 million years ago in what is now Patagonia, Argentina. Image credit: Luis Rey / Yale University.

“Some of the greatest riddles about dinosaurs pertain to their embryology — virtually nothing is known,” said Prof. Gregory Erickson, a researcher at Florida State University and lead author on the study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Did their eggs incubate slowly like their reptilian cousins — crocodilians and lizards? Or rapidly like living dinosaurs — the birds?”

“We know very little about dinosaur embryology, yet it relates to so many aspects of development, life history, and evolution,” said Dr. Mark Norell, a paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History and co-author on the study.

“But with the help of advanced tools like CT scanners and high-resolution microscopy, we’re making discoveries that we couldn’t have imagined two decades ago. This work is a great example of how new technology and new ideas can be brought to old problems.”

Paleontologists had long theorized that dinosaur incubation duration was similar to birds, whose eggs hatch in periods ranging from 11-85 days. Comparable-sized reptilian eggs typically take twice as long — weeks to many months.

Because dinosaur eggs were large, researchers believed they must have experienced rapid incubation with birds inheriting that characteristic from their dinosaur ancestors.

Prof. Erickson, Dr. Norell and their colleagues decided to put these theories to the test.

To do that, the paleontologists accessed some rare fossils — those of dinosaur embryos.

They looked at the fossilized teeth of two well-preserved embryos of ornithischian dinosaurs: (i) Protoceratops, a pig-sized dinosaur found by the team in the Mongolian Gobi Desert, whose eggs were quite small at 194 grams; and (ii) Hypacrosaurus, a very large duck-billed dinosaur found in Alberta, Canada, with eggs weighing more than 4 kg.

First, the authors scanned the embryonic jaws of the two dinosaurs with CT to visualize the forming dentitions. Then they used an advanced microscope to look for and analyze the pattern of ‘von Ebner’ lines — growth lines that are present in the teeth of all animals, humans included.

This work marks the first time that these growth lines have been identified in dinosaur embryos.

“These are the lines that are laid down when any animal’s teeth develops. They’re kind of like tree rings, but they’re put down daily. And so we could literally count them to see how long each dinosaur had been developing,” Prof. Erickson explained.

Using this method, the team determined that the Protoceratops embryos were about three months old when they died and the Hypacrosaurus embryos were about six months old.

This places non-avian dinosaur incubation more in line with that of their reptilian cousins, whose eggs typically take twice as long as bird eggs to hatch — weeks to many months.

The study implies that birds likely evolved more rapid incubation rates after they branched off from the rest of the dinosaurs.

“The results might be quite different if they were able to analyze a more bird-like dinosaur, like Velociraptor. But unfortunately, very few fossilized dinosaur embryos have been discovered,” the researchers said.

The biggest ramification from the study, however, relates to the extinction of dinosaurs.

Given that these creatures required considerable resources to reach adult size, took more than a year to mature and had slow incubation times, they would have been at a distinct disadvantage compared to other animals that survived the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event.

“We suspect our findings have implications for understanding why dinosaurs went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period, whereas amphibians, birds, mammals and other reptiles made it through and prospered,” Prof. Erickson said.

Source: sci.news