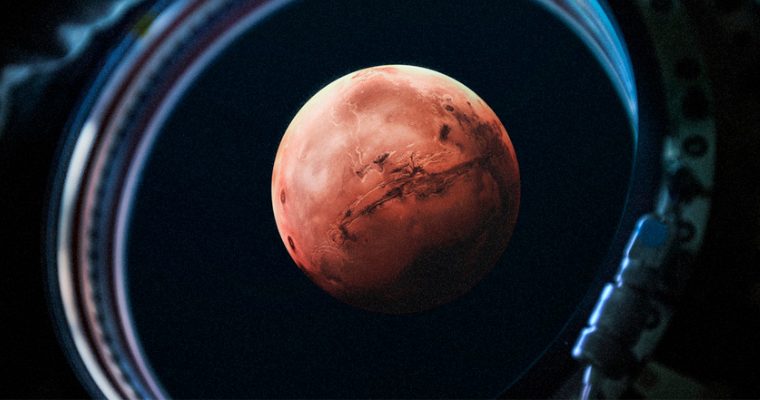

Venus imaged by the Magellan spacecraft. Credit: NASA/JPL

Today Venus has a dry, oxygen-poor atmosphere. But recent studies have proposed that the early planet may have had liquid water and reflective clouds that could have sustained habitable conditions. Researchers at the University of Chicago, Department of Geophysical Sciences, have built a new time-dependent model of Venus’s atmospheric composition to explore these claims. Their findings have been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Water is everywhere in our solar system, usually in the form of ice or atmospheric gas, though occasionally in liquid form. On all of the planets, many of the moons, from the outer ring of the inner asteroid belt to the icy Kuiper Belt, and way out to the far distant Oort cloud two light years away, water is there.

Venus is a hot, dry, rocky planet, a little smaller than our own, with only trace amounts of water vapor in its thick CO2 atmosphere, and previous studies have attempted to model its atmospheric past. Drastically different climatic pictures emerge depending on how the past models were built.

Venus may have always been an uninhabitable hot mess, losing its oxygen to absorption during the crystallization of its magma ocean and never forming liquid water on its surface. Without any way to sequester carbon, ever-increasing atmospheric CO2 wrapped the planet in a thick heavy blanket which led to current atmospheric pressures at the surface 92 times greater than on Earth, making Venus hotter than Mercury despite being twice as far from the sun. Even eventual pelting by icy comets would not be enough to keep water on the surface.

Then again, other models suggest that in the early solar system, when solar radiation was 30% less, Venus may have had a moderate surface temperature with a much thinner atmosphere and bodies of liquid water on its surface—perhaps oceans—as recently as 700 million years ago, before a runaway greenhouse effect boiled it away.

The researchers at the University of Chicago decided to tackle the question with a model of their own. They took the unique approach of first assuming that there once was an ocean with a habitable climate, filling the computer model with a multitude of different ocean levels, and progressing those oceans through three different processes of evaporation and oxygen removal. They ran the model with three different time-dependent starting points, a total of 94,080 times, with a scoring system that allowed them to identify the runs with outcomes closest to the actual current-day atmosphere of Venus.

According to the study results published in PNAS, out of 94,080 runs, only a few hundred were within range of the actual Venus atmosphere we see today. The hypothetical habitable eras on Venus needed to end before 3 billion years ago with a maximum ocean depth of 300 meters across its entire surface (total hydrosphere). The results suggest that Venus has been uninhabitable for more than 70% of its history, four times longer than some previous estimates.

Scientists are reasonably confident that liquid water on a rocky planet is needed for life to exist, as we have one example of life on a wet rocky planet and nothing else to compare it with. Life on Earth is thought to have started around 3.5 to 4 billion years ago, according to the fossil record, and back further still to around 4.5 billion years ago when estimating the molecular clock of evolution. If Venus did have liquid water on its surface 3 billion years ago, it could have harbored life as well.

Source: phys.org