Paleontologists have unearthed the partial skeleton of an enantiornithine (opposite bird) that lived in what is now Utah approximately 75 million years ago (Late Cretaceous epoch). According to an analysis of the fossil, published in the journal PeerJ, Late Cretaceous enantiornithines were the aerodynamic equals of the ancestors of today’s birds, able to fly strongly and agilely.

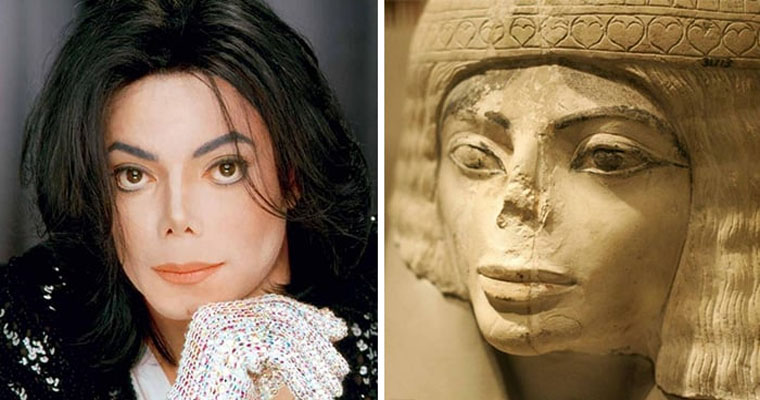

A reconstruction of Mirarce eatoni perched on the horns of the ceratopsian dinosaur Utahceratops gettyi. Image credit: Brian Engh, dontmesswithdinosaurs.com.

All birds evolved from feathered theropods — the two-legged dinosaurs like T. rex — beginning about 150 million years ago, and developed into many lineages in the Cretaceous period, between 146 and 65 million years ago.

But after the cataclysm that wiped out most of the dinosaurs, only one group of birds remained: the ancestors of the birds we see today.

Why did only one family survive the mass extinction? The newly-discovered fossil from one of those extinct bird groups, enantiornithines, deepens that mystery.

“This particular bird, named Mirarce eatoni, is about 75 million years old — about 10 million years before the die-off,” said Dr. Jessie Atterholt, a researcher at the Western University of Health Sciences.

“One of the really interesting and mysterious things about enantiornithines is that we find them throughout the Cretaceous period, for roughly 100 million years of existence, and they were very successful.”

Mirarce eatoni is among the largest North American birds from the Cretaceous; most were the size of chickadees or crows.

The specimen was found in Kaiparowits Formation in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Garfield County, Utah, in 1992, and is the most complete enantiornithine collected in North America to date.

“Most birds from the Americas are from the Late Cretaceous and known only from a single foot bone, often the metatarsus. This fossil was almost complete, missing only its head,” the paleontologists said.

Mirarce eatoni’s breast bone or sternum, where flight muscles attach, is more deeply keeled than other enantiornithines, implying a larger muscle and stronger flight more similar to modern birds.

The wishbone is more V-shaped, like the wishbone of modern birds and unlike the U-shaped wishbone of earlier avians and their dinosaur ancestors. The wishbone or furcula is flexible and stores energy released during the wing stroke.

“What is most exciting, however, are large patches on the forearm bones. These rough patches are quill knobs, and in modern birds they anchor the wing feathers to the skeleton to help strengthen them for active flight,” Dr. Atterholt said.

This is the first discovery of quill knobs in any enantiornithine bird, which tells us that Mirarce eatoni was a very strong flier.

“We know that birds in the early Cretaceous, about 115 to 130 million years ago, were capable of flight but probably not as well adapted for it as modern birds,” Dr. Atterholt said.

“What this new fossil shows is that enantiornithines, though totally separate from modern birds, evolved some of the same adaptations for highly refined, advanced flight styles.”

If enantiornithines in the late Cretaceous were just as advanced as modern birds, however, why did they die out with the dinosaurs while the ancestors of modern birds did not?

One recently proposed hypothesis argues that they were primarily forest dwellers, so that when forests went up in smoke after the asteroid strike that signaled the end of the Cretaceous period — and the end of non-avian dinosaurs — the enantiornithines disappeared as well.

“I think it is a really interesting hypothesis and the best explanation I have heard so far,” Dr. Atterholt said.

“But we need to do really rigorous studies of enantiornithines’ ecology, because right now that part of the puzzle is a little hand-wavey.”

Source: sci.news