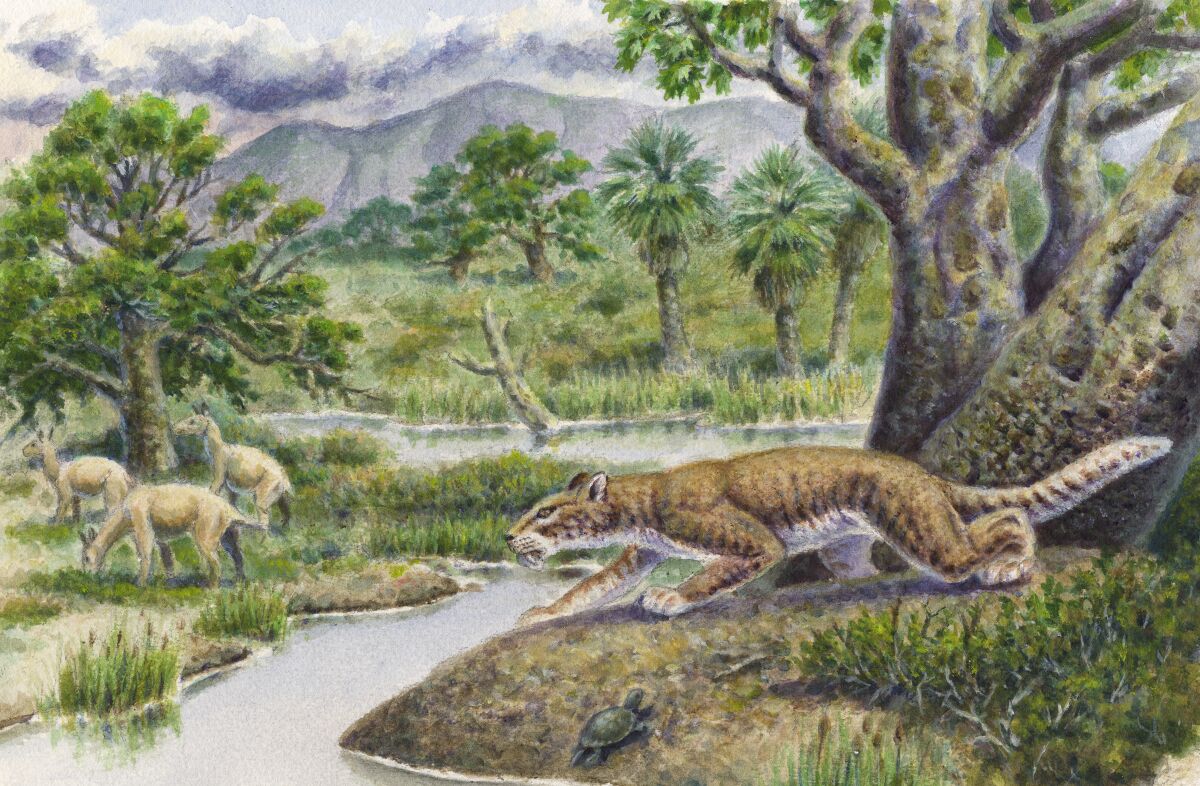

The meat-slicing back teeth of the new saber-toothed catlike species Pangurban egiae, foreground, compared well with the slightly larger teeth of a related sabretooth false-cat Hoplophoneus at the San Diego National History Museum.

(Courtesy of Cypress Hansen/San Diego Natural History Museum )Studying the puma-sized Pangurban egiae, which roamed the local area 38 million years ago, could shed light on how similar predators emerged and then died off

Last spring, a small lower jawbone in the vast fossil collection of the San Diego Natural History Museum was identified as that of a newly discovered saber-toothed catlike predator that roamed the coastal rainforests of San Diego some 42 million years ago.

Working with two other scientists to discover the Diegoaelurus, or “San Diego’s cat,” was a thrill for Ashley Poust, who has worked at the museum as a postdoctoral researcher since 2019. But a more recent discovery of a second new saber-toothed species in the museum’s fossil archives has been just as exciting and important.

Poust said the latest discovery hints at the potential for even more saber-tooth surprises hidden in the museum’s collection of 1.5 million fossils and still buried underground nearby. The more examples of different saber-tooth species that Poust and his colleagues can uncover in the San Diego County fossils, the more complete these land mammals’ evolutionary puzzle will become.

“San Diego has become an incredible resource for saber-tooth evolution,” Poust said on Monday. “San Diego has a lot to tell us. There are teases of both modern cats and saber-teeth true cats.”

The latest saber-tooth discovery was announced in a scientific paper published Oct. 12 in the science journal “Biology Letters.” Co-authored by Poust, Paul Z. Barrett of the University of Oregon and Susumu Tomiya of Kyoto University in Japan, the paper introduced the new species known as Pangurban egiae. The trio discovered this new species through their combined research on a small fossil that includes two teeth attached to part of an upper jawbone. It was uncovered in 1997 at a construction project in Scripps Ranch and had sat unidentified in the fossil collection ever since.

“The specimen has serrated slicing teeth which have important similarities to later predators,” Poust said. “The teeth tell us that close relatives of today’s living carnivores spread around the world earlier than we believed, and they diversified quickly when they reached new continents like North America.”

The Pangurban belongs to an extinct group of carnivores known as Nimravids, or sabre-tooth false-cats. The Pangurban was a catlike predator that roamed the local area about 38 million years ago and it ranged in size between that of the modern-day lynx and puma. Pangurban would have had long, blade-like canine teeth for hunting animals like camels, early horses, and the last North American primates.

By comparison, the Diegoaelurus fossil, which was unearthed in Oceanside in 1988, was from a group of extinct animals called Machaeroidines, which are the oldest group of saber-toothed mammals. It was about the size of a bobcat, and similar in body type to the fossa of Madagascar, a cousin to the mongoose.

Although there are similarities between the Nimravids like Pangurban and the Machaeroidines like Diegoaelurus — including their saber-like fangs, their hypercarnivorous (meat only) diets and their appearance during the Eocene epoch — there are also many differences. The Pangurban, for example, is more closely related to today’s modern cats than the Diegoaelurus, though is not a direct ancestor.

“Nimravids were the cats before cats,” coauthor Barrett said, in a statement. “The importance of Nimravids lies in understanding how ecosystems can push carnivores to such extreme diets and body shapes.”

Pangurban’s discovery stands out, Poust said, because it represents some of the earliest evidence of “hypercarnivory” in the direct relatives of modern meat-eating mammals. With Pangurban, scientists can better understand why and how this radical adaptation evolved and spread. For example, the Pangurban fossil suggests that the decline of forests and primates in North America might have created opportunities for these carnivores to thrive.

Both Diegoaelurus and Pangurban lived during the Eocene epoch, which stretched from 56 million to 34 million years ago. In Eocene times, the San Andreas Fault hadn’t yet begun shifting the Pacific and North American plates, so Baja California was still attached to mainland Mexico and the land mass that is now San Diego would have been farther south and would have been a vast flood plain covered with dense rainforests.

“The Eocene rocks of Southern California are proving to be an important window into the evolution of sabre-tooth carnivory,” said Poust, who said a major construction project now under way in Otay Mesa to create a new border crossing is already turning up new land mammal fossil fragments, which he looks forward to studying someday. Under state law, contractors are required to have paleontologists onsite at major earth digs to ensure any fossils found at the construction site are preserved.

Unlike the Diegoaelurus, which has a simple name drawn from where it was found, the Pangurban egiae’s unusual name is a tribute to both an ancient poem and a contemporary scientist. Poust came up with the main genus name, Pangurban, from the 9th century Irish poem “Pangur Bán” about a monk distracted from his work by his cat, Pangur, who hunts and kills a mouse. The second, or species, name “egiae” was inspired by Japanese scientist and fossil mammal expert Dr. Naoko Egi.

San Diego County was also once home to a third extinct saber-tooth catlike species called the Smilodon, which is more famously known as the saber-tooth tiger. It lived during the Pleistocene epoch, which stretched from 2.5 million years ago to just 10,000 years ago. Modern humans showed up in North America about 13,000 years ago.

Poust said there have been periods of ancient history when saber-tooth species disappeared entirely from the fossil record for millions of years, then returned with no explanation. He believes finding more examples of these extinct species could help explain why these “cat gaps” in time occurred, and how species found evolutionary strategies to survive as the environment changed around them.

“The rise of hypercarnivores against a backdrop of disappearing primates highlights how intertwined the evolutionary paths of major mammalian groups are,” paper co-author Tomiya said in a statement. “This insight from the past raises the stakes for biodiversity conservation in the present. For example, if we lose two-thirds of the planet’s living primate species, which are currently threatened with extinction, it could change the course of evolution for other groups of animals, and thus have profound, cascading effects that last for millions of years.”

Poust said the stressed ecosystems and movement of species during the time of the Pangurban resemble the changes that are happening in our environment today.

“As environmental shifts multiply, some animals will see that as an opportunity,” Poust said. “We can’t say which will be the long-term winners as ecosystems change, but the discovery of Pangurban reminds us how quickly invasion and adaptation can occur and the large role it has played in the history of life.”

Source: sandiegouniontribune.com