Ever since its launch in 1990, the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope has been an interplanetary weather observer, keeping an eye on the ever-changing atmospheres of the largely gaseous outer planets. And it’s an unblinking eye that allows Hubble’s sharpness and sensitivity to monitor a kaleidoscope of complex activities over time. Today new images are shared of Jupiter and Uranus.

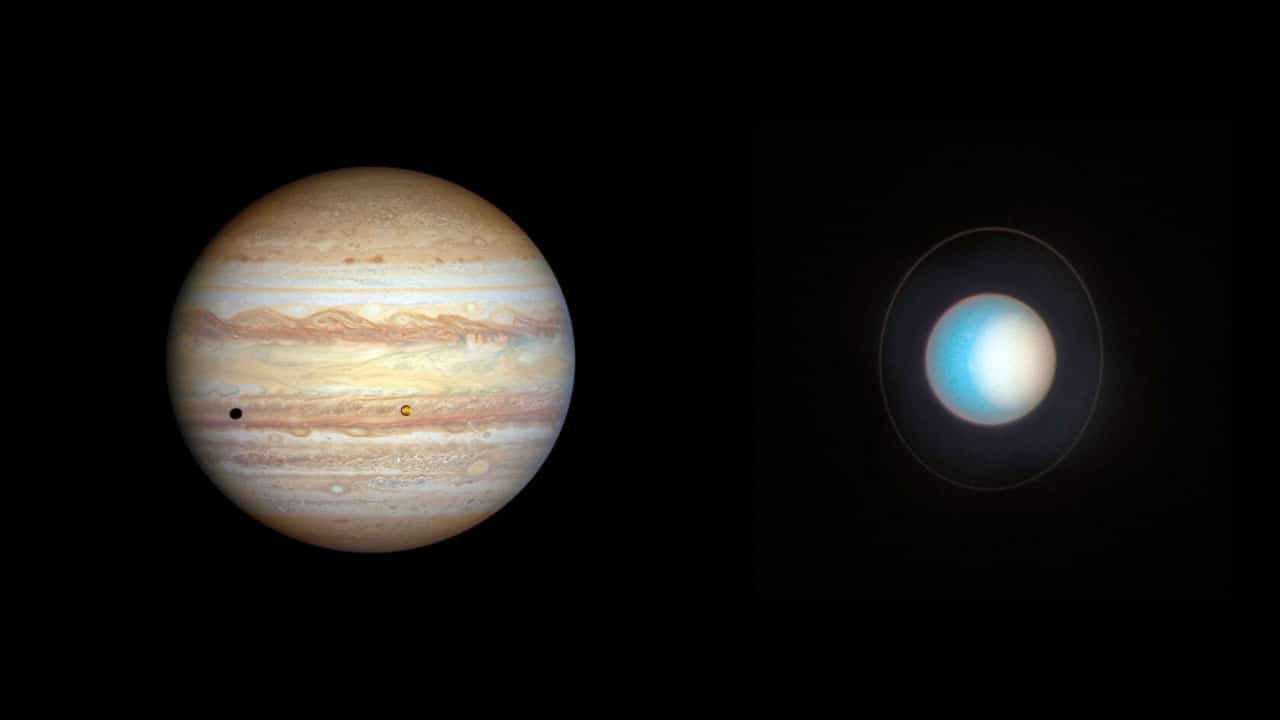

The outer planets beyond Mars do not have solid surfaces to affect weather as on Earth. And sunlight is much less able to drive atmospheric circulation. Nevertheless, these are ever-changing worlds. And Hubble — in its role as interplanetary meteorologist — is keeping track, as it does every year. Jupiter’s weather is driven from the inside out, as more heat percolates up from its interior than it receives from the Sun. This heat indirectly drives colour-change cycles in the clouds, like the cycle that’s currently highlighting a system of alternating cyclones and anticyclones. Uranus has seasons that pass by at a snail’s pace because it takes 84 years to complete one orbit about the Sun. But those seasons are extreme, because Uranus is tipped on its side. As summer approaches in the northern hemisphere, Hubble sees a growing polar cap of high-altitude photochemical haze that looks similar to the smog over cities on Earth.

Inaugurated in 2014, the Hubble Space Telescope’s Outer Planet Atmospheres Legacy (OPAL) programme has been providing us with yearly views of the giant planets. Here are some recent images.

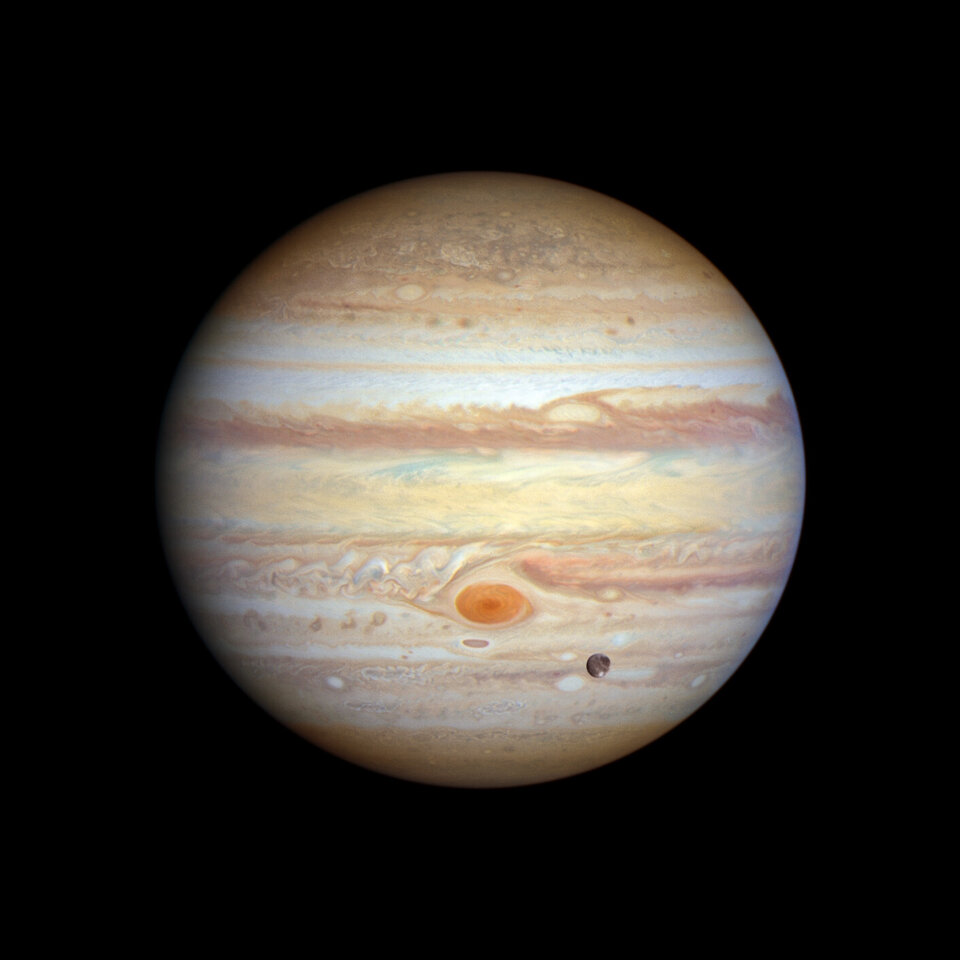

Hubble image of Jupiter (November 2022 and January 2023)

Hubble image of Jupiter (November 2022 and January 2023) Jupiter (January 2023)

Jupiter (January 2023) Uranus (November 2014 and November 2022)

Uranus (November 2014 and November 2022)

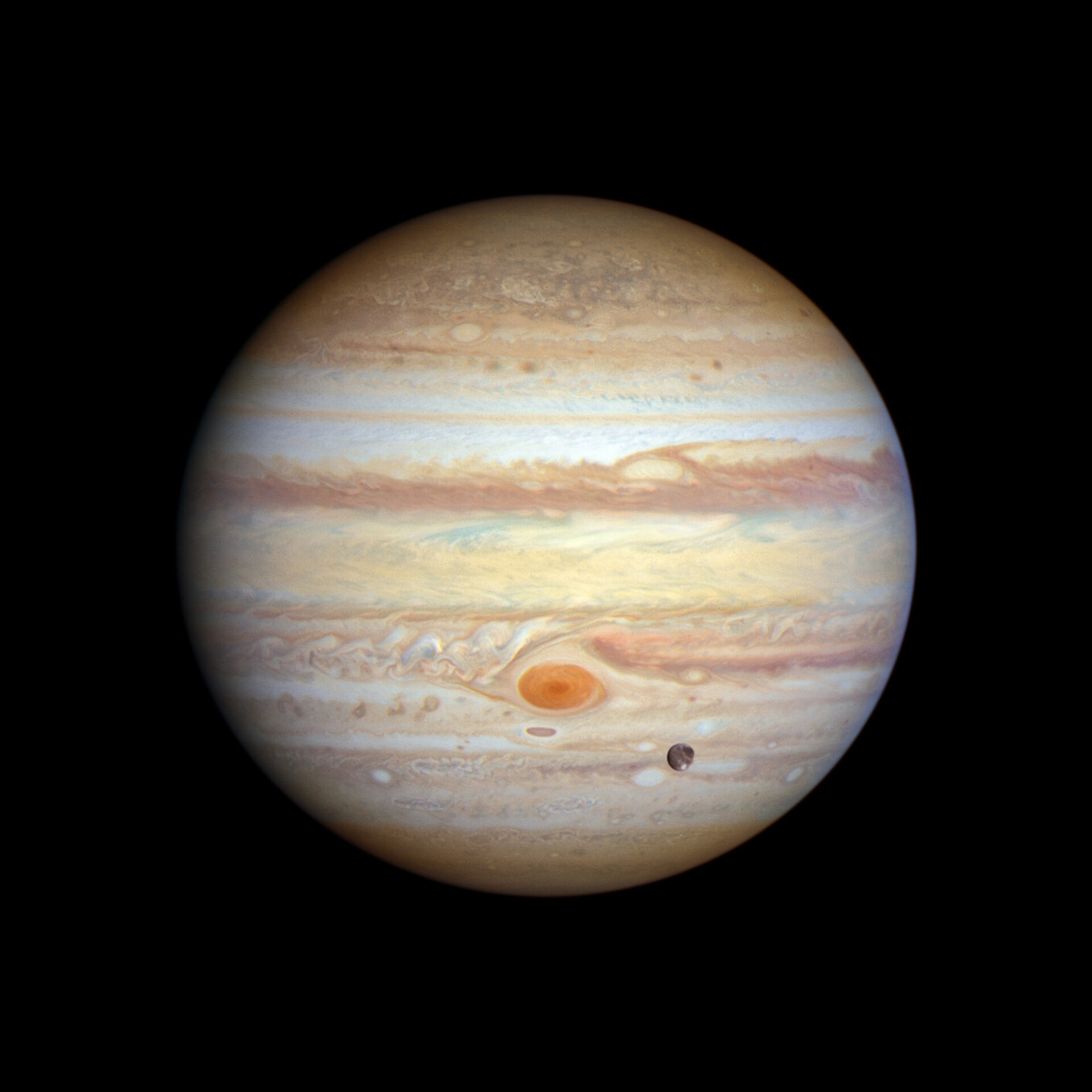

Jupiter Image 1: Jupiter (November 2022)

Image 1: Jupiter (November 2022)

[Image 1] – The forecast for Jupiter is for stormy weather at low northern latitudes. A prominent string of alternating storms is visible, forming a ‘vortex street’ as some planetary astronomers call it. This is a wave pattern of nested cyclones and anticyclones, locked together like the alternating gears of a machine moving clockwise and counterclockwise. If the storms get close enough to each other and merge together, they could build an even larger storm, potentially rivalling the current size of the Great Red Spot. The staggered pattern of cyclones and anticyclones prevents individual storms from merging. Activity is also seen interior to these storms; in the 1990s Hubble didn’t see any cyclones or anticyclones with built-in thunderstorms, but these storms have sprung up in the last decade. Strong colour differences indicate that Hubble is seeing different cloud heights and depths as well.

The orange moon Io photobombs this view of Jupiter’s multicoloured cloud tops, casting a shadow toward the planet’s western limb. Hubble’s resolution is so sharp that it can see Io’s mottled-orange appearance, the result of its numerous active volcanoes. These volcanoes were first discovered when the Voyager 1 spacecraft flew by in 1979. The moon’s molten interior is overlaid by a thin crust through which the volcanoes eject material. Sulphur takes on various hues at different temperatures, which is why Io’s surface is so colourful. This photo was taken on 12 November 2022.

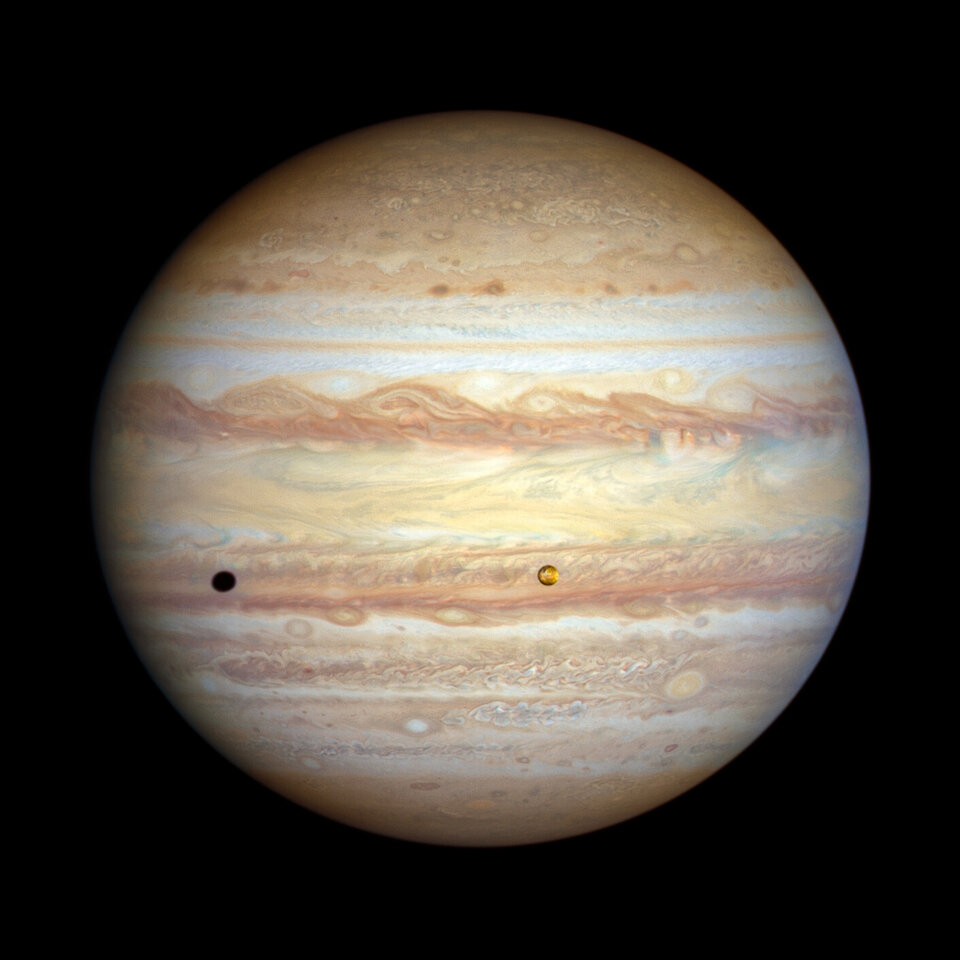

Image 2: Jupiter (January 2023)

Image 2: Jupiter (January 2023)

[Image 2] – Jupiter’s legendary Great Red Spot takes centre stage in this view. Though this vortex is big enough to swallow Earth, it has actually shrunk to the smallest size it has ever been according to observation records dating back 150 years. Jupiter’s icy moon Ganymede can be seen transiting the giant planet at lower right. Slightly larger than the planet Mercury, Ganymede is the largest moon in the Solar System. It is a cratered world and has a mainly water-ice surface with apparent glacial flows driven by internal heat. This image was taken on 6 January 2023.

Jupiter and its large ocean-bearing moons (Ganymede, Callisto and Europa) are the target of ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice). Preparations are currently underway to ready Juice for liftoff from Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana on 13 April 2023. Ganymede is the main target of Juice. As humanity’s next bold mission to the outer Solar System, Juice will complete numerous flybys around Ganymede, and eventually enter orbit around the moon. The mission will explore various key topics: Ganymede’s mysterious magnetic field, its hidden ocean, its complex core, its ice content and shell, its interactions with its local environment and that of Jupiter, its past and present activity, and whether or not the moon could be a habitable environment.

Uranus

Planetary oddball Uranus rolls around the Sun on its side as it follows its 84-year orbit, rather than spinning in a more ’vertical’ position as Earth does. Its weirdly tilted ‘horizontal’ rotation axis is angled just eight degrees off the plane of the planet’s orbit. One recent theory proposes that Uranus once had a massive moon that gravitationally destabilised it and then crashed into it. Other possibilities include giant impacts during the formation of the planets, or even giant planets exerting resonant torques on each other over time. The consequences of Uranus’s tilt are that for stretches of time lasting up to 42 years, parts of one hemisphere are completely without sunlight. When the Voyager 2 spacecraft visited during the 1980s, the planet’s south pole was pointed almost directly at the Sun. Hubble’s latest view shows the northern pole now tipping toward the Sun.

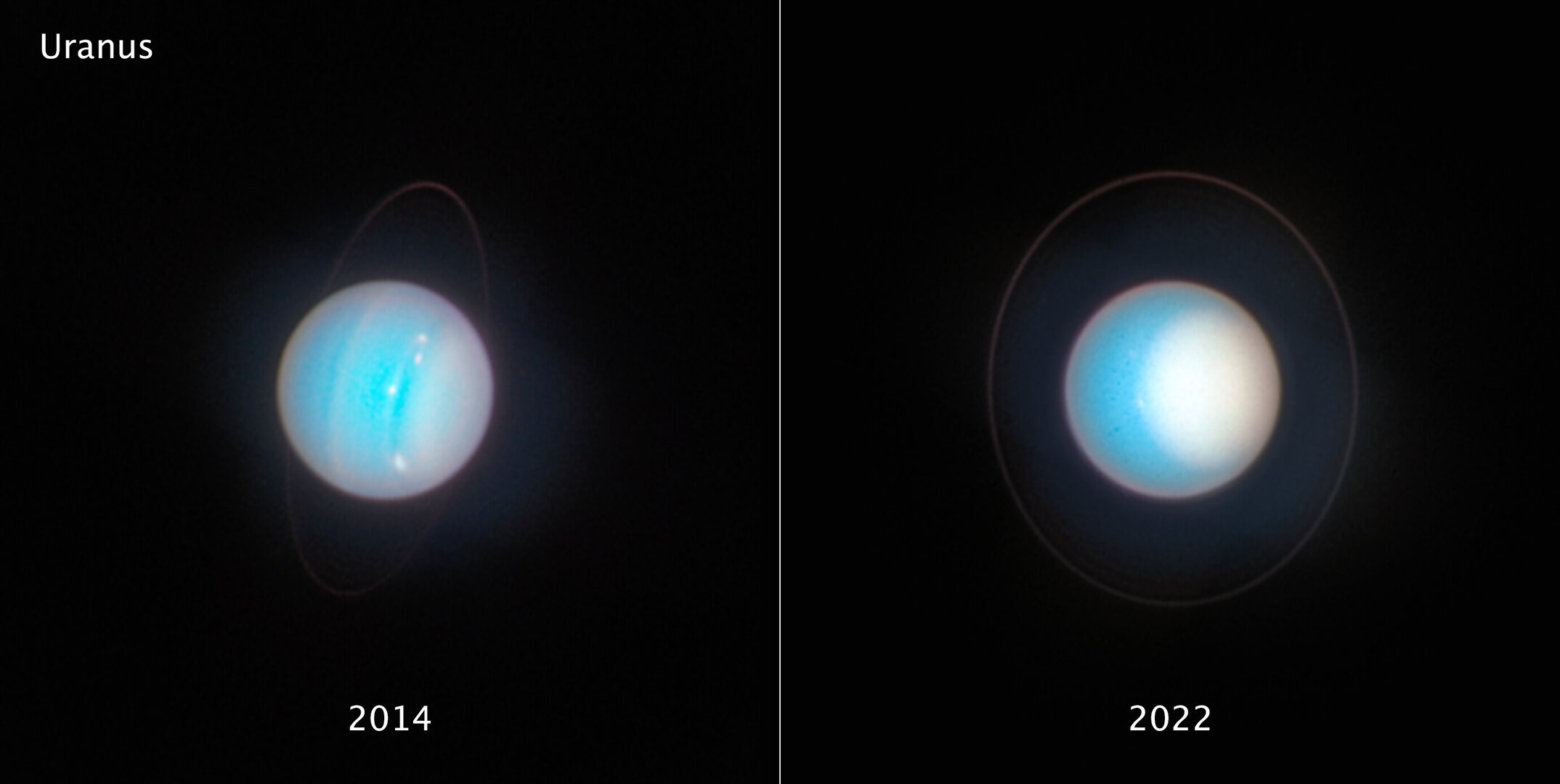

Image 3: Uranus (November 2014)

Image 3: Uranus (November 2014)

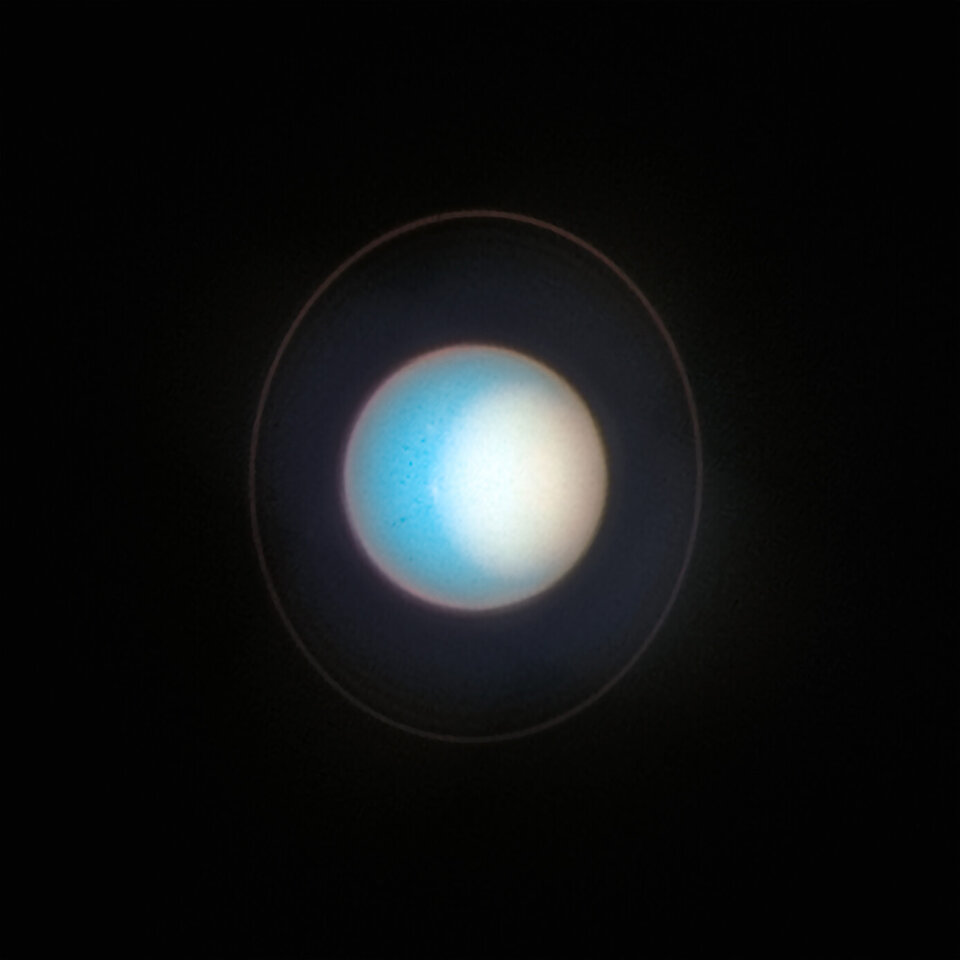

[Image 3] – This is a Hubble view of Uranus taken in 2014, seven years after the northern spring equinox when the Sun was shining directly over the planet’s equator, and shows one of the first images from the OPAL programme. Multiple storms with methane ice-crystal clouds appear at mid-northern latitudes above the planet’s cyan-tinted lower atmosphere. Hubble photographed the ring system edge-on in 2007, but the rings are seen starting to open up seven years later in this view. At this time, the planet had multiple small storms and even some faint cloud bands.

[Image 4] – As seen in 2022, Uranus’s north pole shows a thickened photochemical haze that looks similar to the smog over cities. Several little storms can be seen near the edge of the polar haze boundary. Hubble has been tracking the size and brightness of the north polar cap and it continues to get brighter year after year. Astronomers are disentangling multiple effects — from atmospheric circulation, particle properties, and chemical processes — that control how the atmospheric polar cap changes with the seasons. At the Uranian equinox in 2007, neither pole was particularly bright. As the northern summer solstice approaches in 2028 the cap may grow brighter still, and will be aimed directly toward Earth, allowing good views of the rings and the north pole; the ring system will then appear face-on. This image was taken on 10 November 2022.