The BMW Museum is the first port of call for any petrolhead visiting Munich. But there’s an even more extraordinary collection of machinery just down the road, at the BMW Group Classic headquarters.

The BMW Museum is the first port of call for any petrolhead visiting Munich. But there’s an even more extraordinary collection of machinery just down the road, at the BMW Group Classic headquarters.

Set inside the original Bayerische Motoren Werke factory, BMW Group Classic houses offices, archives, conference rooms and a café. But it’s also home to a small gathering of rare and vintage BMW motorcycles and cars, and a couple of laboratory-level workshops.

Access to this remarkable hoard is by special appointment only—but on this day we had one such appointment. And it was during a behind-the-scenes tour that I stumbled upon this vintage beauty.

Access to this remarkable hoard is by special appointment only—but on this day we had one such appointment. And it was during a behind-the-scenes tour that I stumbled upon this vintage beauty.

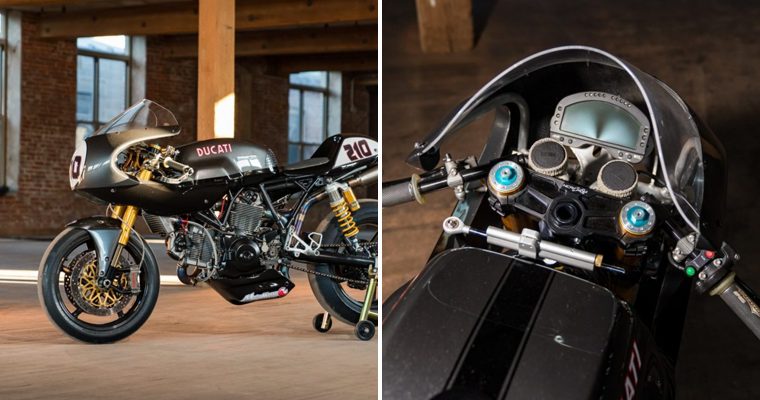

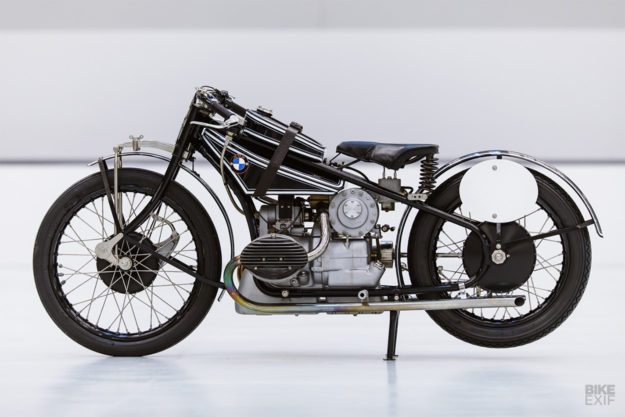

To be honest, at first I had no idea what I was looking at. So our guide graciously explained the history of the supercharged 1929 BMW WR 750 Kompressor. Then he threw in a plot twist: this isn’t a restored WR 750, but a complete nuts and bolts replica.

It’s been executed so well, even an expert would find it virtually impossible to tell it apart from the real deal.

It’s been executed so well, even an expert would find it virtually impossible to tell it apart from the real deal.

The WR stands for Werksrennmotorräder (works race bike), which is exactly what the WR 750 was. It was a technological tour-de-force, built to take on speed records and racing championships. They got the former right; Ernst Jakob Henne set a land speed record of 134.68 mph on a WR 750 in 1929.

The WR 750 had a 750 cc four stroke flat twin with overhead valves, a supercharger wedged between the seat and gearbox, and a single carb. It had no rear suspension, and a leading link front fork with twin leaf spring assemblies. Groundbreaking stuff, back then.

The WR 750 had a 750 cc four stroke flat twin with overhead valves, a supercharger wedged between the seat and gearbox, and a single carb. It had no rear suspension, and a leading link front fork with twin leaf spring assemblies. Groundbreaking stuff, back then.

The thing is, an original WR 750 is impossible to come by. Which is why collector, racer and master fabricator Jürgen Schwarzmann decided to build one from scratch.

So he joined forces with friends Alfons Zwick and Erich Frey, and the trio eventually ended up creating a small series of WR 750 replicas (the exact number of which is a closely guarded secret).

So he joined forces with friends Alfons Zwick and Erich Frey, and the trio eventually ended up creating a small series of WR 750 replicas (the exact number of which is a closely guarded secret).

Their first challenge was finding a blueprint to work from. Only two of Ernst Henne’s original record-breaking machines still exist: one belongs to BMW, and the other is in the Deutsches Museum.

Both existing bikes are land speed racers, modified for straight-line glory. So they are distinctly different from the road racers that Schwarzmann wanted to replicate.

Both existing bikes are land speed racers, modified for straight-line glory. So they are distinctly different from the road racers that Schwarzmann wanted to replicate.

Bits and pieces from the pre-war race bikes do pop up on the radar from time to time. But they’re rarely for sale, and are a far cry from a complete bike. And documentation is sparse too, even in the BMW Group Classic’s extensive archives.

So the trio’s first task was a virtual puzzle build, documenting everything they could about the WR 750 before they even picked up a spanner. Their primary goal was to recreate the bike as accurately as possible, and to make it fully functional.

So the trio’s first task was a virtual puzzle build, documenting everything they could about the WR 750 before they even picked up a spanner. Their primary goal was to recreate the bike as accurately as possible, and to make it fully functional.

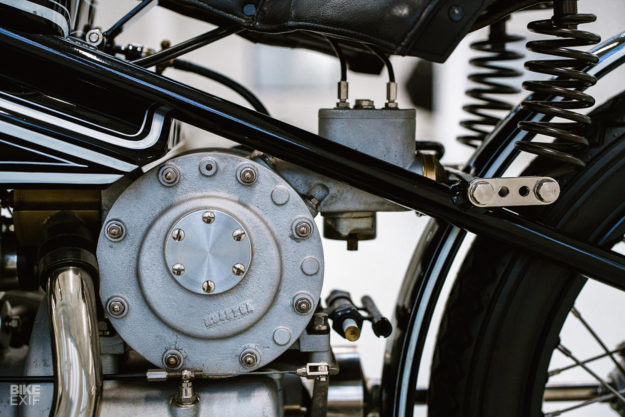

Once the build itself was underway, each man had a specific portfolio. Frey is an experienced engine designer; he would measure and sketch up parts from what was available, and machine the motor and gearbox’s casings and internals.

Schwarzmann would handle the chassis, and Zwick would tackle pattern making, molds, cast parts, and the final drive assembly.

Schwarzmann would handle the chassis, and Zwick would tackle pattern making, molds, cast parts, and the final drive assembly.

Recreating the chassis was never actually part of the plan. The guys had intended to simply replicate the WR 750 motor, then wedge it into a different pre-war BMW frame. But then documentation surfaced indicating the chassis was unique to this bike, and so—for the sake of authenticity—they went all in.

And they really did go deep. Fred Jakobs, the head of the BMW Group Classic archive, gives some insight: “My personal highlight is the perfection in every detail. So you could exchange every part of the replica with an original part, and it fits and it works.”

And they really did go deep. Fred Jakobs, the head of the BMW Group Classic archive, gives some insight: “My personal highlight is the perfection in every detail. So you could exchange every part of the replica with an original part, and it fits and it works.”

“There was no compromise. For example, they made their own screws, because in the 1920s they used special screw threads that were normally used in BMW aircraft engine production. This was not necessary, but for me it’s a sign that they strived for one hundred percent perfection.”

Every last detail has been replicated. The unique sump curves forward to trace the fender’s lines. The linked braking system has adjustable bias.

Every last detail has been replicated. The unique sump curves forward to trace the fender’s lines. The linked braking system has adjustable bias.

The leather tank strap, the BMW roundels, and even the font used for the numbers stamped into the casings are all straight out of 1929.

BMW themselves supported the project, because, as Jakobs puts it, “We knew about the professional skills of the people involved. And also we knew about their integrity.”

BMW themselves supported the project, because, as Jakobs puts it, “We knew about the professional skills of the people involved. And also we knew about their integrity.”

“So there was no doubt that they had no commercial interest and made the bikes only for themselves, and two pieces for the BMW collection.”

It took six years before the guys were able to fire up their first engine, and a total of ten years before their work was done, and a limited series had been built—some mit Kompressor, and some ohne Kompressor.

It took six years before the guys were able to fire up their first engine, and a total of ten years before their work was done, and a limited series had been built—some mit Kompressor, and some ohne Kompressor.

Schwarzmann himself completed several laps on a Kompressor version at the Nürburgring, taking it easy to preserve the motor.

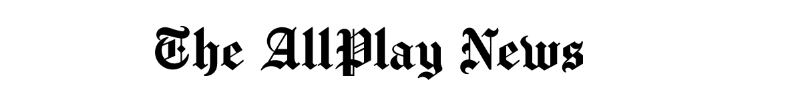

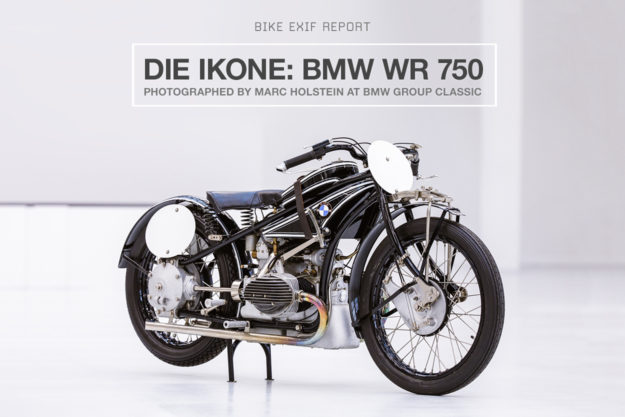

Fast forward to this year, when our good friend Marc Holstein snuck into BMW Group Classic and wheeled the WR 750 Kompressor into one of the halls, ready to document this truly spezial motorcycle.

Fast forward to this year, when our good friend Marc Holstein snuck into BMW Group Classic and wheeled the WR 750 Kompressor into one of the halls, ready to document this truly spezial motorcycle.

Enjoy the pictures.

Images by Marc Holstein | BMW Group Classic | Facebook | BMW Welt (Museum) Instagram

Source: Resurrection: The BMW WR 750 Kompressor, by Dr. Scott Williams, Classic BMW Motorräder, Volume 39, Number 2.