The discovery of a 3,000-year-old civilization at Sanxingdui raised profound questions about China’s ancient past. Now, researchers believe they’re finally close to finding some answers.

SICHUAN, Southwest China — Xu Feihong has spent the last decade working at archaeological sites all over China. But his latest dig is unlike anything he’s experienced.

Each morning, the 31-year-old begins his shift by ducking inside a giant air-conditioned glass dome. He pulls on a full hazmat suit, surgical gloves, and a face mask. Then, he lays down flat on a wooden board and is slowly winched down into a deep pit.

The archaeologist has spent weeks digging while hanging horizontally inches above the soil — like he’s doing an impression of Tom Cruise in “Mission Impossible.” The elaborate precautions ensure that nothing — not even a stray hair, or a bead of sweat — contaminates the precious earth beneath him.

“This is the fanciest dig I’ve ever seen,” Xu tells Sixth Tone. “The level of resources devoted to it is astonishing — and unique. Only Sanxingdui deserves it.”

China is lavishing funding on Xu and his team for good reason. The researchers, who are based at a remote site near the southwestern city of Chengdu known as Sanxingdui, believe they’re close to unlocking one of Chinese archaeology’s greatest mysteries.

In the 1980s, a group of researchers found two pits at Sanxingdui crammed full of strange relics: piles of elephant tusks, gold masks, and bronze figures with wild, bulging eyes. The objects were 3,000 years old, and unlike anything previously uncovered in China.

The finds were just the beginning. Other teams have since unearthed traces of more artifacts, large buildings, and even a city wall. It appears that Sanxingdui was once the capital of a powerful and technologically advanced civilization, which flourished in the region around the time of the Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun.

Yet the kingdom’s origins remain unknown. Ancient Chinese historians barely mentioned the Southwest, dismissing the region — then known as Shu — as an obscure backwater. And the artifacts themselves offer few clues. No written materials have ever been found at Sanxingdui.

For decades, the riddle of Sanxingdui has fascinated China. Theories about how the civilization emerged have proliferated, with some speculating the settlement was founded by travelers from Egypt – or even extra-terrestrials. But in the absence of clear archaeological evidence, these debates appeared destined to remain unresolved.

Until now. In 2019, researchers made another stunning discovery: six additional pits located close to the two uncovered in the ’80s. Like the originals, they appear to be sacrificial sites filled with ritual artifacts.

“When we cleared off the topsoil, the sight in front of me was really shocking,” says Xu Feihong. “You never see so many ivories and bronze artifacts packed so densely together.”

For the team, the new pits represent a golden opportunity. The latest excavations have already produced several striking finds, which have generated enormous public interest. More importantly, researchers will be able to analyze the dig sites using a range of scientific techniques that weren’t available when Pits 1 and 2 were discovered.

Every object inside the new pits — as well as the surrounding soil — is being painstakingly collected, dated, and sealed in air-tight containers, before being sent for analysis. More than 30 research institutes from across China have cleared their laboratories to receive the samples.

The hope is that cutting-edge material analysis will provide unprecedented insights into these artifacts — and the people who buried them. Though researchers are trying to remain calm, the answers to many decades-old questions may finally be within reach.

A Forgotten Civilization

It has taken nearly a century to reach this point. The first discoveries near Sanxingdui were made as far back as 1929, yet it took over half a century for the site’s true significance to be recognized.

The initial finds were made by Yan Daochang, a farmer who worked a small plot of land north of Chengdu in a place named Moon Bay. While digging a well, Yan uncovered a large stash of jade artifacts.

Some of these jades found their way into the hands of private collectors and caught the attention of archaeologists in the region. In 1933, David Crockett Graham, a Christian missionary and academic based in Chengdu, organized an excavation at Yan’s farm. The dig unearthed hundreds more pieces of jade, stone, and pottery.

In China, however, ancient religious sites are hardly a rarity. Though local cultural bureaus continued to organize archaeological surveys at Moon Bay through the ’50s and ’60s, the finds didn’t cause much of a stir.

The turning point came after the Cultural Revolution. In 1986, workers at a brick factory near Moon Bay unearthed yet another cache of jade relics and reported the find to the Sichuan Archaeological Institute.

The institute dispatched a few researchers to the factory, which sat on top of a hillock known as Sanxingdui, or “Three Stars Mound.” There, they found a hole measuring 4.5 meters by 3.3 meters — what would later become known as the “No. 1 Sacrificial Pit.”

The researchers eventually extracted 420 fragments of artifacts from the pit, including hundreds of seashells, gold scepters, and bronze molds of human faces. Then, a month later, they found a second pit near the first containing an even stranger collection of objects.

Under the topsoil lay dozens of elephant tusks, covering a densely packed layer of bronzes. The objects — which included a mix of vessels, sculptures, and figurines — appeared to have been deliberately smashed and burned before being buried, a practice the archaeologists had never seen before.

Many other surprises awaited them. Over the following weeks, the researchers pulled 1,500 objects out of Pit 2. By the time they finished, it had begun to dawn on them that they’d made one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of the 20th century.

The haul included some truly jaw-dropping objects, including a towering bronze sculpture of a tree with dagger-like leaves and birds nesting among its carved branches. The tree, which is over 4 meters tall and weighs more than 800 kilograms, is the largest bronze artifact from the period ever unearthed worldwide.

But the prize find was a huge bronze statue known as the Large Standing Figure — a giant, intricately detailed rendering of a man standing 2.6 meters tall and weighing nearly 200 kilograms.

The statue, which today looms over the central hall of the Sanxingdui Museum, continues to baffle researchers. It depicts a solemn-looking figure with glaring eyes and a hooked nose — features that are distinct from other Chinese artifacts from the period. It is dressed in three layers of clothes, their delicate patterns still visible on the cold, hard bronze.

Most mysterious of all is the statue’s pose. The figure’s disproportionately large hands are raised in front of its chest, its fingers forming two circles. It looks like the figure was once holding something aloft, but researchers still have no idea what.

Some guess the statue was gripping a cong — an oblong piece of jade used in religious rites — while others suggest an ivory tusk. Archaeologists also remain uncertain how Sanxingdui acquired so many tusks, as elephants aren’t native to that part of China — or, at least, they aren’t anymore.

Because of its unique style and enormous size, many experts argue the statue is a representation of the supreme leader of the Sanxingdui civilization, who combined the roles of god, king, and shaman.

Ever since this breakthrough excavation in 1986, field surveys of the area surrounding Sanxingdui have continued ceaselessly. Archaeologists have found evidence that the area was once home not just to a site for making religious offerings — as the pits appear to have been used — but also to a human settlement spanning at least 12 square kilometers.

In 2013, a few kilometers from the sacrificial pits, researchers discovered rows of unusual marks in the shape of a giant Roman numeral three. The area, named Qingguanshan terrace, is the highest point of the Sanxingdui site.

These marks are believed to be the remains of walls and pillars from a cluster of buildings. One of the structures was around 65 meters long, making it one of the largest Bronze Age buildings ever found in China, according to Guo Ming, a Shanghai-based archaeologist who participated in the excavation.

Given its huge scale, many experts suggest the Qingguanshan structure was likely a palace. But Guo is skeptical. The marks indicate the building only had side doors; most palaces from the period had doors on their front facades. She hypothesizes it may have in fact been a state-owned warehouse for storing treasure or weapons — a less glamorous, but still important find.

“We’re finding more and more archaeological evidence suggesting the architecture (in ancient China) was more complex and diverse in its functions than we previously understood,” says Guo. “While palaces are certainly very important, functional buildings like warehouses and workshops are equally valuable to our understanding of ancient history and societies.”

Surrounding the Qingguanshan buildings and sacrificial pits, meanwhile, are a string of human-built mounds, which archaeologists suspect to be the remains of a city wall.

Unraveling the Mystery

Each new discovery has only left archaeologists with more questions about Sanxingdui. They now have enough evidence to conclude an affluent, sophisticated civilization thrived in the area for nearly 1,000 years, up to around the 11th century B.C.

But since no written records from the city have been found, the story of Sanxingdui — its origins, history, and culture — remains entirely blank.

In ancient Chinese sources, there are references to a remote kingdom named Shu based in what is now modern-day Sichuan province. The “Chronicles of Huayang,” compiled during the Jin dynasty (266-420 A.D.), writes that the Shu state originated in the upper reaches of the Min River — a tributary of the Yangtze that runs through Sichuan province — over 3,500 years ago. Over the next millennium, five dynasties ruled Shu, before the kingdom gradually declined and was conquered by the Qin state in 316 B.C., according to the “Chronicles.”

Yet ancient Chinese descriptions of Shu offer few details. Most surviving stories about the kingdom are mythological, such as the tale of King Duyu, who transformed into a cuckoo after his death and sang every spring to remind farmers to sow their seeds on time.

Even when sources do mention the Shu state, they tend to dwell mainly on its remoteness. Given Sichuan province’s mountainous topography, travel to the region would have been challenging. The Chinese poet Li Bai summed up the kingdom’s reputation in his 8th-century A.D. work “Hard Roads in Shu”:

Oh, but it is high and very dangerous!

Such traveling is harder than scaling the blue sky …

Until two rulers of this region

Pushed their way through in the misty ages,

Forty-eight thousand years had passed

With nobody arriving across the Qin border.

Until the discovery of Pits 1 and 2 in 1986, historians had assumed the Shu state was mythical. Now, however, as a consensus develops that Sanxingdui was likely once part of the Shu kingdom, archaeologists are revisiting these ancient sources.

“We can’t really use archaeological discoveries to prove an ancient myth,” says Yu Mengzhou, an archaeologist at Sichuan University who is assisting the excavations at Sanxingdui. “But these old tales may provide some clues.”

But Sanxingdui doesn’t appear to have been the hermit-like kingdom described by Chinese poets. Though artworks like the Large Standing Figure are unique, many other finds indicate that Sanxingdui was part of a complex trade network that spread across East Asia.

Jade artifacts found in the sacrificial pits are similar in style to those uncovered as far away as Zhejiang province, nearly 2,000 kilometers to the east. And the seashells filling the pits, which at the time were used as a form of currency, are believed to have originated in South Asia.

The sketchy historical record has left room for more esoteric theories about Sanxingdui to flourish. For years, a conspiracy theory claiming the site is the remains of an alien civilization has been circulating in China.

According to this theory, extra-terrestrials came to Earth over 5,000 years ago and built a string of settlements along the 30th parallel north. This led to the creation of the Egyptian pyramids, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Mayan civilization, as well as the lost city in Sichuan province. The aliens then exited the planet through a wormhole in Bermuda, the story goes.

Despite carbon dating showing the sacrificial pits were made 2,000 years after the aliens’ supposed stay on Earth, the alien hypothesis has gained significant traction on the Chinese internet.

A more reasonable theory posits that Sanxingdui was founded by foreign settlers. Zhu Dake, a renowned cultural scholar affiliated with Shanghai’s Tongji University, has suggested the city was built by travelers from the Middle East or ancient Egypt.

Sanxingdui sculptures emphasize their subjects’ eyes in a similar way to artifacts found in ancient Egypt, Zhu notes. The ivories and gold scepters found in the sacrificial pits, meanwhile, share some characteristics with Middle Eastern relics.

But the majority of Chinese archaeologists disagree with Zhu. So far, no evidence has been found of human migration or even economic exchanges between Sanxingdui and Western Asia.

“The spread of civilization and the spread of cultural elements are totally different things,” says Xu Jian, the Shanghai University archaeologist. “For example, we have Coca-Cola in China, but that doesn’t mean that Chinese civilization was imported from the United States, much less that we’re Americans.”

In the absence of more evidence, these debates have remained deadlocked for years. That, however, is why the recent discovery of six more sacrificial pits at Sanxingdui has triggered such excitement.

Resurrecting the Relics

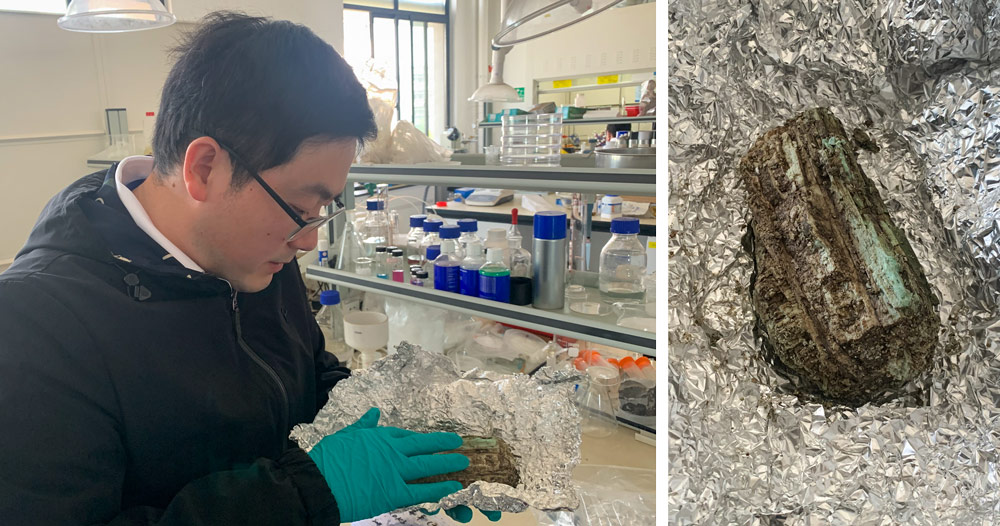

In a whitewashed room on Shanghai University’s campus, Ma Xiao fishes inside a refrigerator and pulls out a plastic container. Inside, wrapped in aluminum foil in the style of a leftover burrito, is a small sample of elephant tusk Ma’s team extracted from a pit at Sanxingdui three months ago.

Archaeologists view 3,000-year-old ivories like this one as potential goldmines of information about Sanxingdui’s culture, especially the religious rituals its inhabitants once performed.

The huge number of elephant tusks inside the sacrificial pits is one of Sanxingdui’s most unusual features. In Pit 3 — the site Xu Feihong excavates using his “Mission Impossible” pose — more than 100 tusks have already been unearthed.

But until recently, researchers couldn’t learn much about the ivories. The act of removing the objects from the ground would destroy them.

When Pits 1 and 2 were excavated in 1986, the dig team pulled out dozens of tusks, stacked them in wooden crates, and stored them in a warehouse. But over the following years, the tusks began to deteriorate, with several shattering into pieces.

“No one knew how to preserve the ivory, and even now we’re still trying to figure that out,” explains Ma, as he slowly unwraps the aluminum foil. “The tusk underneath has a texture similar to a croissant — tiny flakes fall off at every touch.”

Material scientists like Ma are playing a key role in studying the fragile artifacts. After analyzing the tusks under a modern microscope, Ma found the objects’ apparently smooth exteriors are in fact covered with tiny cracks. All the organic material inside the ivory, such as protein, has degraded after centuries underground, and has been replaced by particles of soil and water.

“The mud and water are holding the ivory together,” Ma says.

Much of the elaborate equipment being used at Pit 3, such as the air conditioned glass dome, is designed to prevent the relics from suffering a sudden drop in water content when they’re removed from the damp soil. Such evaporation can be catastrophic, as archaeologists excavating the Terra-cotta Army in Xi’an have also found. Scientists are also designing new materials and protocols to protect the ivory.

“It’s a very difficult task that’s going to take years,” Ma says. “It’s like these relics are sick, and scientists are their doctors. But unlike human patients, relics can’t tell you where they’re hurt.”

Preserving the tusks will give archaeologists more time to study them, which they hope will allow them to gain new levels of understanding. Analyzing how the ivories were laid out inside the pits — why, for example, some were piled on top of each other, while others weren’t — could provide fresh insights into Sanxingdui’s religious beliefs, says Xu Jian, the Shanghai University archaeologist.

Paleontologists also hope new isotope analysis techniques will allow them to work out where the elephant tusks came from and how they were removed from the animals.

“We’re using the best of our imaginations to restore a culture we barely know,” says Xu Jian. “Every bit of information could be important.”

Reimagining Chinese History

As the excavations at Sanxingdui progress, more revelations surely await. The new pits have already produced several startling finds, including an enormous bronze mask over a meter wide — one of the largest artifacts of its kind ever uncovered.

But archaeologists are holding their breath for one discovery above all: any sign of a Sanxingdui writing system.

The lack of written materials inside the sacrificial pits has surprised researchers. Given Sanxingdui’s apparent sophistication and trade with other Chinese kingdoms, the fact that not a single written character has been found is remarkable.

Ran Honglin, a site manager at the current excavations in Sanxingdui, is convinced the ancient city kept some kind of written records, but speculates they may not have survived. While members of contemporary civilizations like the Shang — a kingdom based in central China — carved characters onto oracle bones, the people of Sanxingdui may have used a less durable material.

“Running such a huge site, with such a wealth of artifacts, would have required sophisticated social organization,” says Ran. “To make this system function smoothly, there must have been good communication systems, which is difficult to achieve without writing.”

There are signs the people of Sanxingdui were smarter than many realize, Ran adds. They appear to have had a keen interest in math, and an obsession with the number three in particular.

Artifacts in the sacrificial pits were divided into three layers. The enormous bronze statue of a tree uncovered in Pit 2 has three levels, each containing three branches, with a total of nine sacred birds sitting among them. The number of many other kinds of artifacts found inside the pits have been multiples of three.

The hunt for written materials is one reason why Xu Feihong and his team at Pit 3 are collecting every grain of dirt at the dig. Each one may contain traces of ink-filled silk or papyrus that degraded over the centuries, but which modern chemical analysis techniques might be able to identify.

If written records are discovered at Sanxingdui one day, it will be a game-changer for Chinese archaeology. The characters would finally allow the ancient civilization to speak with its own voice.

Yet, despite the fact so much about Sanxingdui remains shrouded in mystery, its discovery has already significantly altered our understanding of early Chinese history.

For centuries, the Shang dynasty — the first Chinese kingdom for which written and archaeological evidence exists — was considered the true cradle of Chinese civilization, whose influence then gradually spread across East Asia.

But recent archaeological research — including the findings at Sanxingdui — has shown that several powerful kingdoms existed in China 3,000 years ago alongside the Shang. These civilizations, moreover, had regular exchanges with each other.

As a result, archaeologists now paint a very different picture of Bronze Age China: It was not a world divided between Shang and barbarian tribes, but a diverse space — or a “sky full of stars,” as some scholars describe it — in which multiple ancient kingdoms coexisted and competed for resources.

“We used to divide the world of the past into pieces and try to judge what was passed from A to B,” says Wang Xianhua, director of Shanghai International Studies University’s Institute of the History of Global Civilization. “But in fact, our ancestors lived in a shared world just like we do.”

Tang Jigen, a chief researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ Institute of Archaeology, says these states were all comparably strong. On the Central Plains, there was the Shang; in eastern China, the Hu Fang; and in the Southwest, the Shu. In fact, oracle bones inscriptions from the Shang contained explicit references to Shu and Hu Fang.

“They belonged to one cultural circle, which is the Bronze Age civilization of East Asia,” says Tang. “But at the same time, each state had its own culture and ideology.”

Standing in the center of the Sanxingdui Museum, the large bronze figure gazes down impassively. Perhaps one day, we will understand the role his people played in that formative era. But for now, he maintains his cool silence.