Researchers at the Philadelphia-based Penn Museum are figuratively sweeping the skeletons out of their closets. A 6,500-year-old human skeleton that had been stored up in the basement for 85 years was recently uncovered by museum personnel.

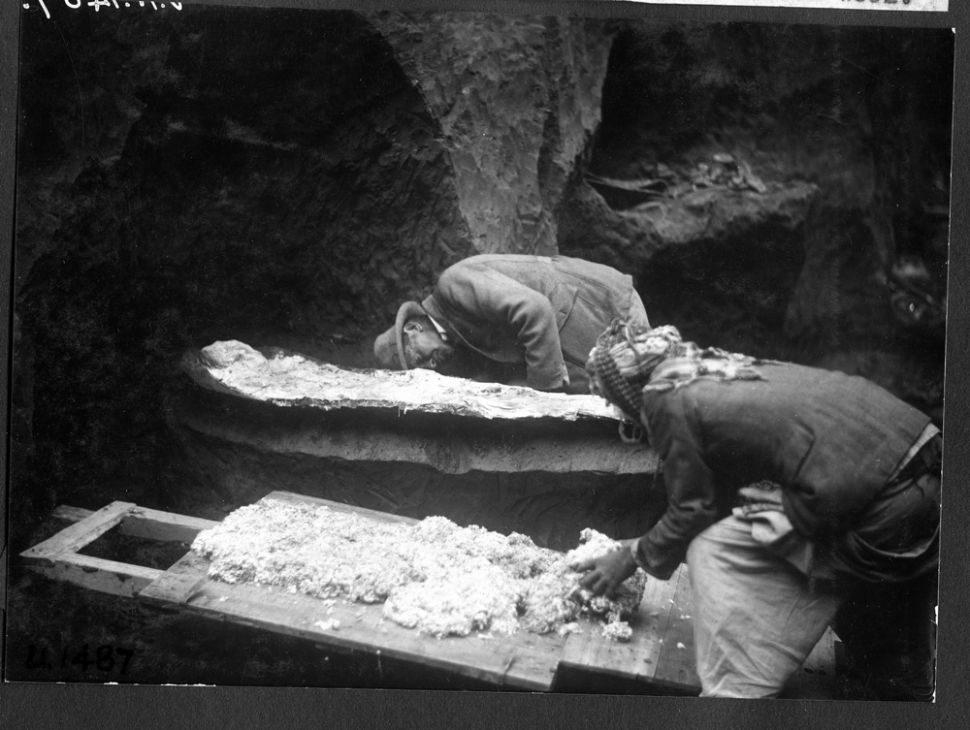

A 6,500-year-old skeleton was unearthed at the Ur site in Iraq. Here, the skeleton was coated in wax in the field and lifted whole along with surrounding dirt.

A 6,500-year-old skeleton was unearthed at the Ur site in Iraq. Here, the skeleton was coated in wax in the field and lifted whole along with surrounding dirt.

The wooden box was hidden in a storage area and lacked a catalog card or identification numbers. However, recent efforts to digitize some of the museum’s ancient archives have revealed fresh details regarding the background of the enigmatic box and the skeleton inside, known as “Noah.”

According to the documents, Sir Leonard Woolley and his group of archaeologists from the Penn and British Museums first discovered the human remains inside the box between 1929 and 1930 at the site of Ur in contemporary Iraq.

The famed Mesopotamian “royal cemetery,” which had hundreds of graves and 16 tombs loaded with cultural artifacts, was discovered during Woolley’s excavation, which is best known for this discovery. But the archaeologist and his group also came upon graves that were buried about 2,000 years before Ur’s royal cemetery.

A lightweight plaster mixture is placed over the covered skeleton, the 6,500-year-old human remains discovered at the Ur site in Iraq, in order to protect it during shipping. The silt is already being cut away under the skeleton to make room for the carrying board.

Nearly 50 feet (15 meters) below the surface of the ruins of Ur, in a flood plain, the crew discovered 48 burials from the Ubaid era, which spanned roughly 5500 to 4000 B.C.

Woolley chose to remove just one skeleton from the location, despite the fact that remains from this time period were exceptionally uncommon even in 1929. Wax was applied to the bones and the surrounding earth before being packaged and sent to Philadelphia and finally London.

The teeth of the 6,500-year-old skeleton are well-preserved, as seen in this view of the upper body and skull.

The teeth of the 6,500-year-old skeleton are well-preserved, as seen in this view of the upper body and skull.

A set of lists outlined where the artefacts from the 1929 to 1930 dig were headed — while half of the artefacts remained in Iraq, the others were split between London and Philadelphia.

One of the lists stated that the Penn Museum was to receive a tray of mud from the excavation, as well as two skeletons.

But when William Hafford, the project manager responsible for digitalizing the museum’s records, saw the list, he was puzzled. One of the two skeletons on the list was nowhere to be found.

Further research into the museum’s database revealed the unidentified skeleton had been recorded as “not accounted for” as of 1990. To get to the bottom of this mystery, Hafford began exploring the extensive records left by Woolley himself.

After locating additional information, including images of the missing skeleton, Hafford approached Janet Monge, the Penn Museum’s curator of physical anthropology. But Monge, like Hafford, had never seen the skeleton before.

That’s when Monge remembered the mysterious box in the basement.

When Monge opened the box later that day, she said it was clear the human remains inside were the same ones listed as being packed up and shipped by Woolley.

The skeleton, she said, likely belonged to a male, 50 years or older, who would have stood somewhere between 5 feet 8 inches (173 centimetres) to 5 feet 10 inches (178 cm) tall.

Penn Museum researchers have nicknamed the re-discovered skeleton “Noah,” because he is believed to have lived after what archaeological data suggests was a massive flood at the original site of Ur.

New scientific techniques that weren’t yet available in Woolley’s time could help scientists at the Penn Museum determine much more about the time period to which these ancient remains belonged, including diet, ancestral origins, trauma, stress and diseases.

Source: thearchaeologist.org