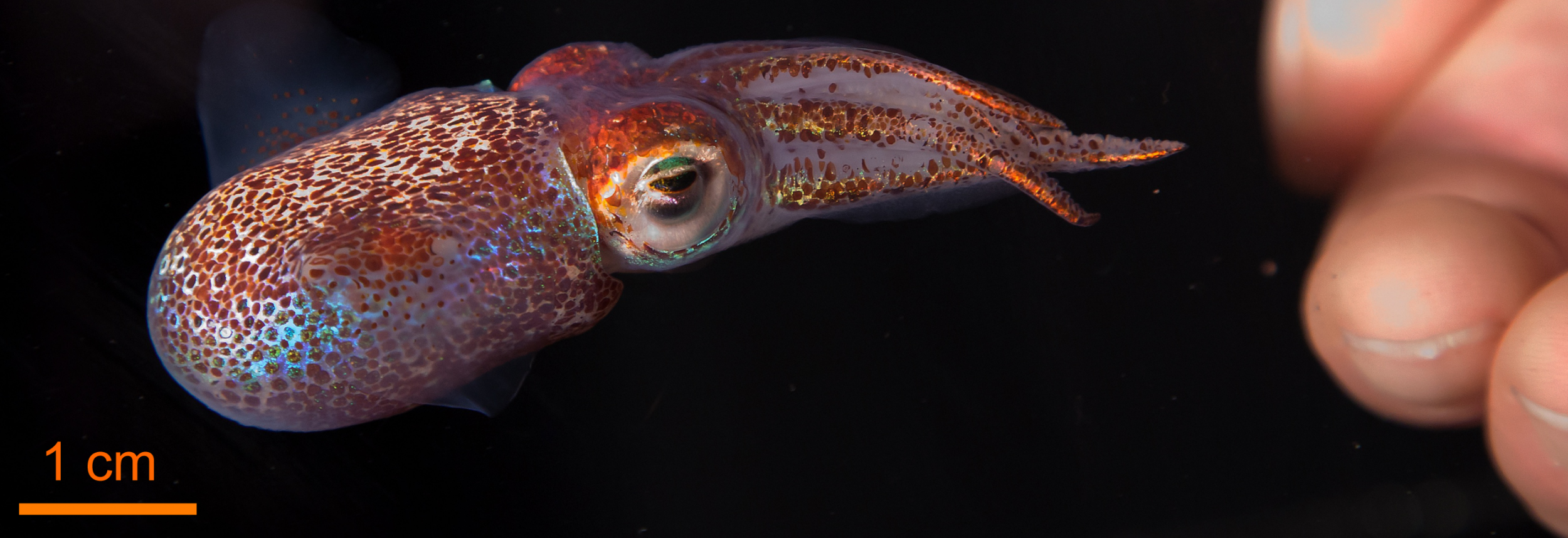

Self-camouflage is just one of the tricks of Brenner’s bobtail squid, a newly found species that is also helping research into microbes in the human gut

Bobtail squid are the second smallest group of squid in the world, at between 1cm and 5cm from neck to rounded, stumpy butt, and they only come out at night.

In 2019, scientists named a new species, Brenner’s bobtail squid (Euprymna brenneri), after finding them while night-diving off the Japanese island of Okinawa. “When you shine a light on them, they freeze,” says Oleg Simakov from the University of Vienna, one member of the squid-finding team. This makes them easy to catch in a hand net.

While they might have been easy for the scientists to capture at night, during the day bobtail squid adopt a fascinating form of camouflage. They bury themselves in the seafloor, and flick sand grains over their head and body – sticking them in place with mucus produced by cells in their skin.

If a keen-eyed predator still spies them, they have another trick in their arsenal. By releasing acid from their skin, they quickly shed their gooey, sandy coat, which then hangs in the water as a decoy, distracting the attacker while the squid escapes. At night, when they hunt, the bobtail squid use a different form of disguise: camouflaging themselves against the light of the moon beaming down by switching on dim lights across their bellies.

Brenner’s bobtail squid was named as a new species in 2019. Photograph: Gustavo Sanchez

When scientists brought the living squid from Okinawa into the laboratory, they started sequencing its DNA. “We found that there was one species that didn’t match with any other previously reported,” says Gustavo Sanchez, from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology. On closer examination, this new squid also looks different from the others. The females have enlarged suckers on their arms, something that has previously only been seen in males.

The new species is named after Nobel prize winner, Prof Sydney Brenner, who several members of the team worked with before he died in 2019. Brenner was especially interested in cephalopods, the big-brained group of invertebrates, including squid, octopuses and cuttlefish.

Compared with octopuses, which are aggressive and usually try to eat each other, bobtail squid are much more peaceable and easier to keep in captivity. Studies of other bobtail squid species and their symbiotic glowing bacteria have been giving scientists insights into the relationship between humans and the microbes in our guts.

Brenner’s bobtail squid appeared in a 2021 study that casts light on their evolution. “The lineage that corresponds to this new species can be clearly separated into two groups,” says Sanchez. One in the Mediterranean Sea and Atlantic Ocean, the other, including Brenner’s bobtail squid, in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

“These have different evolutionary roots,” says Sanchez. The two geographically distinct groups of bobtail squid split apart at the end of the Oligocene epoch, roughly 30m years ago, when the ancient Tethys Sea was coming to an end, blocking the connection between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean.