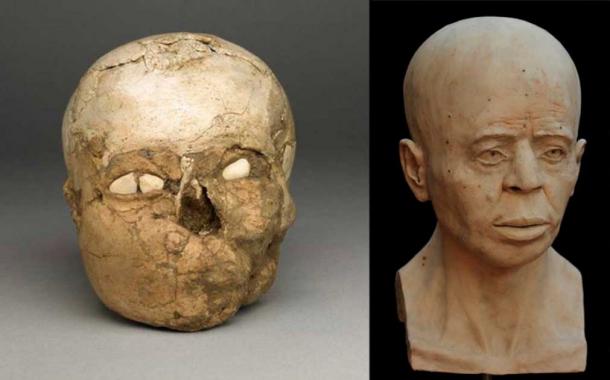

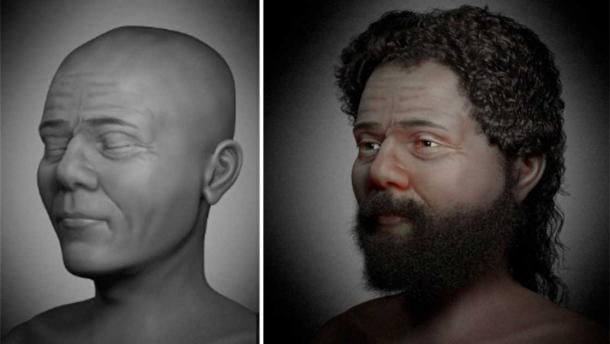

The face of the famous plastered Jericho Skull, which was found in the Palestinian city of Jericho in 1953, has been fully recreated via 3D-imaging technology, revealing exactly what the man to whom the skull belonged looked like when he walked the earth 9,000 years ago. An initial 3D re-creation of the man’s face was created in 2016, but the new image used the latest technology to produce one of the most thorough and accurate facial reconstructions ever made based on an analysis of an ancient human skull.

The Neolithic Reconstruction

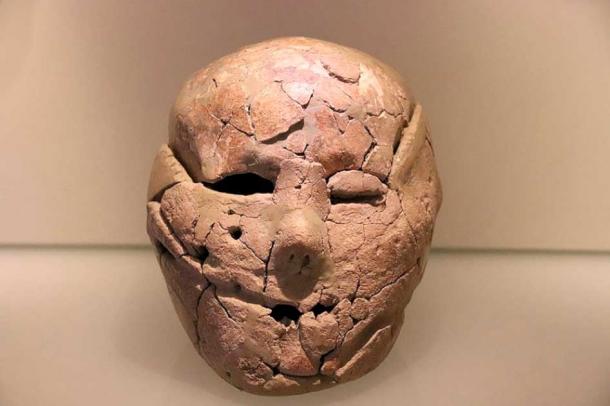

Plastered skulls were a form of artwork commonly produced in the Neolithic period in the city of Jericho (Tell es-Sultan in ancient times). They were made from real human skulls that were filled in and covered with plaster, after which specific features were added to recreate the human face. The idea was to create a permanent plaster image of a living person (usually a beloved parent, grandparent, sibling or child) as a form of sculpture that could be kept around the house indefinitely.

People who lived in the southern Levant (modern-day Israel and Palestine) during the Neolithic period (8,500 BC to 4,300 BC) practiced some elaborate funerary customs. They often buried their family members in graves directly beneath their homes , and in some instances they would remove the heads to make the plaster skull sculptures. These skulls were layered over with a special plaster mixture colored with iron oxide to give it a skin-like color, and the plaster was carefully shaped to make lifelike facial features (cheeks, chins, jaws, noses, etc.). Colorful shells were used to cover the eye sockets, and hair and various facial features were painted on the skulls to recreate the complete look of a living human.

Known simply as the Jericho Skull, the incredible object that was the subject of the new facial reconstruction was unearthed 70 years ago by celebrated British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon . It was one of seven such skulls she discovered at the Tell es-Sultan site in Jericho during her excavations, which at that time were the most extensive to ever take place at that location.

This plastered skull, which in its current condition reveals only a vague outline of a decayed human face, has been held by the British Museum since its original discovery. The seven skulls that were found at the time were all sent to different museums around the world. The first such skull was discovered in the 1930s in Jericho, and as of now approximately 60 plastered skulls have been found at several sites in or around Jericho in the southern Levant.

Modern attempts at Reconstructing the 9,000-year-old Jericho Skull

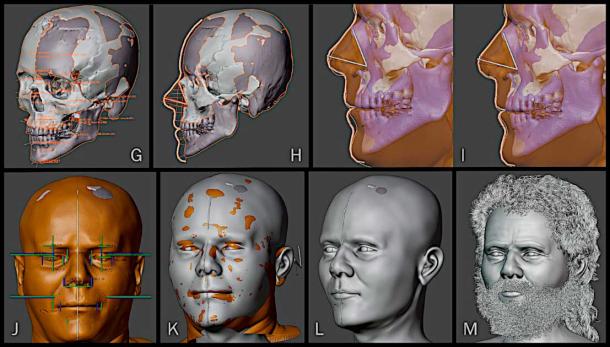

The initial 2016 reconstruction was based on precise measurements of the Jericho Skull, which were obtained using a type of detailed scanning known as micro-computed tomography (micro-CT). With this data researchers were able to create a virtual 3D model of the head and face, approximating how the man would have looked when he was alive.

The new re-creation, which was released to the public in an article published in the journal OrtogOnline in December, used related but somewhat different techniques to make a more realistic and accurate version of the Neolithic man’s head and face. In this case computed tomography (CT) scans were used to harvest data from the skull, and then statistical projections of normal features and anatomical deformations were derived from those CT scan results in order to construct a more vivid and lifelike 3D image.

The team of Brazilian scientists responsible for this exceedingly accurate re-creation included individuals from three separate disciplines: 3D graphics expert Cicero Moraes , who has performed dozens of facial reconstructions of historical figures with the archaeological research group Arc-Team Brazil; dental surgeon Thiago Beaini, who is an associate professor of dentistry at the Federal University of Uberlandia; and Moacie Elias Santos, an archaeologist affiliated with the Ciro Flamarion Cardoso Archaeology Museum in the city of Ponta Grossa.

The new reconstruction has revealed the person to have been a dark-haired man in his 30s or 40s. By today’s standards that would have made him middle-aged. The most unusual feature of the skull was its shape, which was much broader on top and in the back than a normal human head.

Researchers know this shape was obtained through the practice of binding, where an individual’s still-forming skull is wrapped tightly in bandages at an early age to make sure it is reshaped into a particular form. This was a common practice in the Neolithic period, and it would seem it was done primarily for aesthetic purposes (because people thought oddly-shaped skulls were attractive, in other words).

Getting a Closer Look at the Amazing Plaster Skulls of Ancient Jericho

Jericho, which is located 34 miles (55 kilometers) east of Jerusalem in the Palestinian West Bank, is one of the oldest inhabited cities in the world, having first been occupied around 10,000 BC. Kenyon was the first archaeologist to reach the oldest layers of settlement at Tell es-Sultan, and it was during this deep archaeological work that she found the plastered skulls. These fascinating sculptures were made in approximately 7,000 BC, and the care with which they were prepared showed just how serious the Neolithic period residents of ancient Jericho were about preserving the remains of their ancestors, in a form that could be admired and venerated by future generations.

In the Bible (the Book of Joshua), Jericho is identified as the first Canaanite city attacked by the Israelites after they crossed the Jordan River in approximately 1,400 BC. Supposedly, the walls of Jericho collapsed under an Israelite onslaught of shouting and blown trumpets , but archaeological research has failed to find any evidence to suggest any such collapse ever happened.

What archaeologists have found at Jericho, however, is some astounding artifacts that reveal the truth about the ancient funerary practices of the city’s earliest inhabitants, who were living there several thousands of years before the Israelites invaded. More and more plastered skulls have been found as excavations have continued, and in the years to come Cicero Moraes hopes to complete digital reconstructions of at least some of them, using the same techniques he applied to make the image of the Jericho Skull.