To this day, archaeologists don’t know for sure why the massive city of 20,000 people at Cahokia Mounds vanished quickly and left barely any trace behind.

Long before Christopher Columbus “discovered” North America, the mounds of Cahokia stood tall and formed the continent’s first city in recorded history.

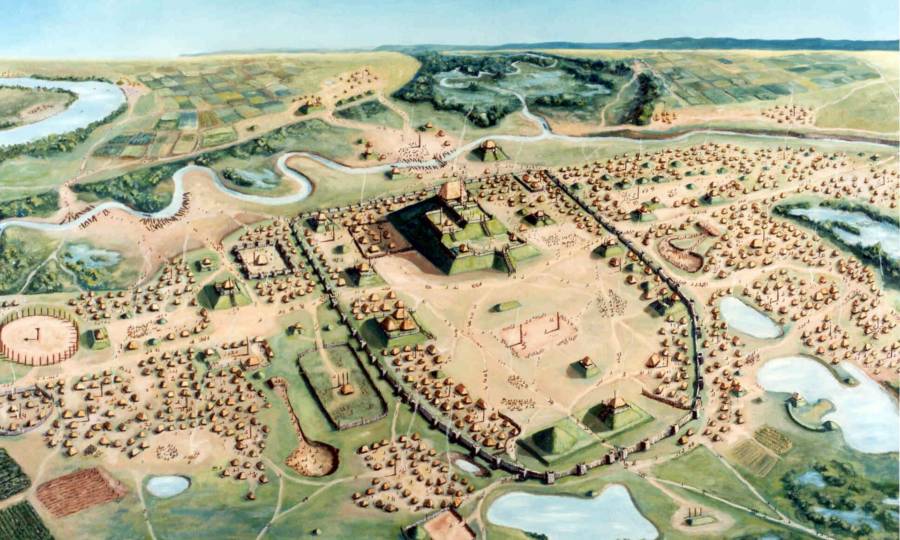

In fact, during its height in the 12th century, Cahokia Mounds was larger in population than London. It spread across six square miles and boasted a population of 10,000 to 20,000 people — vast figures for the time.

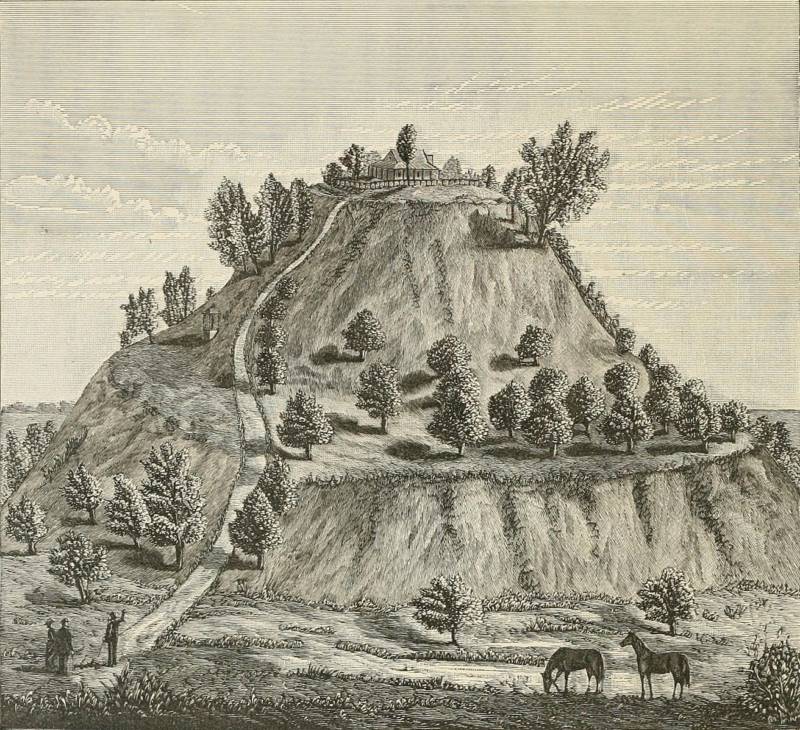

Cahokia Mounds State Historic SiteAn illustration of Cahokia

But Cahokia’s peak didn’t last long. And its demise remains mysterious to this day.

Who Were The People Of Cahokia Mounds?

Situated across the Mississippi River from what is now St. Louis, Cahokia was the biggest pre-Columbian city north of Mexico. Cahokia’s citizenry had no standardized writing system, so archaeologists still largely rely on peripheral data to interpret any artifacts they’ve found that might unlock the city’s mysteries.

The name “Cahokia” itself comes from the aboriginal population that inhabited its area in the 1600s.

Half a millennium earlier, however, the land was home to another society — one which archaeological finds indicate had sophisticated copper work, jewelry, headdresses, stone tables (with engraved birdmen), a popular game called “Chunkey,” and even a caffeinated drink.

The most recent scientific research — a study of fossilized teeth — suggests Cahokians were largely immigrants from the Midwest who possibly traveled from as far as the Great Lakes and the Gulf Coast.

To the south of Cahokia Mounds lay Washausen, an ancient settlement that archaeologists believed to have been abandoned by the time of Cahokia’s peak around 1100.

A History Channel documentary on Cahokia.

It’s quite likely that Earth’s unusual, warmer climate during Cahokia’s popularity was no coincidence. There was more frequent rainfall in the Midwest during this time, and the planet’s temperatures substantially increased as Cahokia’s population grew.

“An increase in average yearly precipitation accompanied by the warmer weather, permitting maize farming to thrive,” wrote Timothy Pauketat and Susan Alt in a paper published in Medieval Mississippians: The Cahokian World.

By 1200, however, the city was on a downturn. Once again, there seemed to have been a directly-correlated climate factor in play here, as a serious flood-plagued the land at the time. Cahokia Mounds was abandoned entirely by 1400, with much of the ancient city still buried under 19th- and 20th-century developments today.

In other words, underneath modern-day Illinois and its tangled web of highways and construction lies America’s first known city.

The Famous Monks Mound

The most immediately apparent remnant of ancient Cahokia near modern-day St. Louis is the 100-foot tall “Monks Mound.” The impressive structure was given this name because a group of Trappist monks lived nearby in historic times, long after the ancient city had thrived.

Much of American history taught in schools paints a broad and simplistic picture of the pre-colonial U.S. According to University of Illinois professor of anthropology Thomas Emerson, however, Cahokia itself — and Monks Mound, specifically — indicates a far more nuanced, sophisticated past than many people realize.

Wikimedia Commons

Monks Mound, the largest manmade pre-Columbian earthen mound in North America.

“A lot of the world is still relating in terms of cowboys and Indians, and feathers and teepees,” he told The Guardian. “But in A.D. 1000, from the beginning, (a city is) laid on a specific plan. It doesn’t grow into a plan, it starts as a plan. And they created the most massive earthen mound in North America. Where does that come from?”

Scientific tests conducted on teeth discovered in the area have indicated that Cahokia’s population was a mix of people from the Natchez, the Pensacola, the Choctaw, and the Ofo tribes of indigenous peoples. They also indicated that a third of them were “not from Cahokia, but somewhere else. And that’s throughout the entire sequence (of Cahokia’s existence).”

Wikimedia CommonsAn 1882 illustration of Monks Mound

Nonetheless, this fruitfully coexisting group of Native Americans traded, hunted, and farmed together. Perhaps most impressively, they implemented rather sophisticated urban planning — using astronomical alignments to design this small metropolis of up to 20,000, replete with a town center, wide plazas, and handmade mounds.

Monks Mound, which covered 14 acres, is still intact today — 600 to 1000 years after its completion. Archaeologists even discovered postholes, suggesting a structure such as a temple may have once sat on top. Monks Mound, a cluster of smaller mounds, and one of the grand plazas were once walled in with a two-mile-long palisade made of wood that required 20,000 posts — just one feature of Cahokia that reveals its massive and sophisticated urban scope.

Human Sacrifice

Situated less than a half mile south of Monks Mound and measuring in at only 10 feet high is Mound 72. This particular mound dates back to somewhere between 1050 and 1150, and contains the remains of 272 people — many of whom were sacrificed.

By all accounts, the practice of human sacrifice was so integral to the culture and spiritual foundation of Cahokia that the remains of more sacrificial victims were found here than in any other place north of Mexico. A thousand years of wear and tear can make it difficult to accurately identify specific sacrifice numbers, but archaeologists are fairly confident in their assertions.

Cahokia Mounds State Historic SiteAn illustrated aerial view of Cahokia.

One incident alone at Mound 72 saw 39 men and women executed “on the spot,” according to Pauketat and Alt.

“It seemed likely the victims had been lined up on the edge of the pit…and clubbed one by one so that their bodies fell sequentially into it.”

Another occasion saw 52 malnourished women between 18 and 23 sacrificed simultaneously. The reasons why are unclear, though analysis of their teeth indicates that they were locals, and hence, not victims of capture, prisoners of war, or otherwise criminally punished.

The remains of several couples and a child were also found here, with one couple’s burial accompanied by 20,000 shell beads. This might indicate they were of high social status or religiously revered.

Religion And Cosmology In Cahokia Mounds

Indeed, the remnants of Cahokia suggest that there were strong religious elements at play in this society.

A series of five wooden circles was constructed to the west of Monks Mound, each built at different times between 900 A.D. and 1100. These woodhenges vary substantially in size, from 12 red cedar wood posts to 60.

Some researchers believe these structures were used as calendars that marked the solstices and equinoxes of the time, to properly satisfy the cultural and religious urges and plan festivals accordingly. It’s posited that a priest figure may have stood on a raised platform in the middle of a henge, for instance.

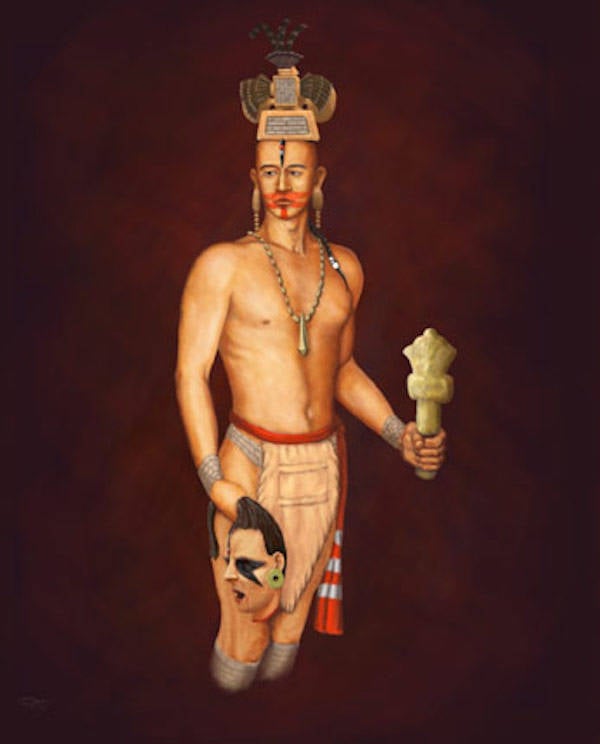

Wikimedia Commons

A Mississippian Era priest holding a ceremonial flint mace and severed human head.

According to an account recorded on the Cahokia Mounds website, sunrise during the equinox is quite the sight to behold from this location. A post from a woodhenge aligns with the front of Monks Mound to the east, making it appear as though the giant mound “gives birth” to the Sun.

While no written records facilitate these theories from garnering definite support, the tangible archaeological finds are more than enough for some researchers to stand firm in their beliefs that Cahokia had a deep cosmological appreciation.

“New evidence suggests that the central Cahokia precinct was designed to align with calendrical and cosmological referents — the sun, moon, earth, water and the netherworld,” a team of archaeologists stated in a paper published in Antiquity in 2017.

Wikimedia Commons

An illustration of a sandstone tablet with a “Birdman” engraving. The tablet was found in 1971 during excavations at Monks Mound.

The “Emerald Acropolis,” as archaeologists have dubbed it, marks “the beginning of a processional route” that leads to the center of Cahokia. A dozen mounds and the remains of wooden buildings (likely “shrines,” according to archaeologists) were denoted at this acropolis as having “lunar alignments.”

Water, too, seemed to have played a central role in the religious life of Cahokians. Some of the buildings were found to have been ritually “closed” with “water-redeposited silts” atop. One of these contained a buried infant, which researchers posited was intended as an “offering.”

A Game Of Chunkey

However, Cahokian life wasn’t all serious and reverential — they seemed to have their fair share of fun and leisure too.

Chunkey, for example, was just one of Cahokia’s many artistic and recreational pastimes. Of course, archaeologists can’t be entirely certain what the 1,000-year-old stone discs believed to be used for chunkey were actually used for, but accounts from the 18th and 19th centuries do detail “chunkey stones” that would be rolled on a field while people threw large sticks at it to see who could get closest.

Points would be awarded in proportion to how close the stick came to the stone — chunkey may very well have been one of the earliest iterations of bocce ball, in other words. Written accounts from the 18th and 19th century even confirmed that gambling on these matches was a standard occurrence.

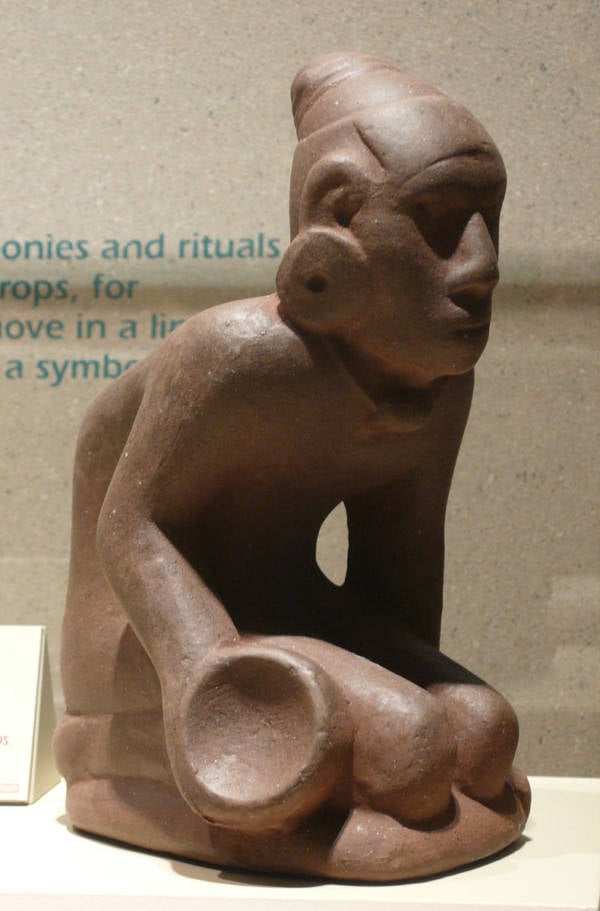

Wikimedia Commons

The “Chunkey Player” statue found in Muskogee County, Oklahoma.

In Pauketat’s estimation, chunkey was played in the grand plaza behind Monks Mound. A vivid description of what he imagined a match to be like, published in Archaeology Magazine, certainly captivates the mind.

“The chief standing at the summit of the black, packed-earth pyramid raises his arms,” wrote Pauketat.

“In the grand plaza below, a deafening shout erupts from 1,000 gathered souls. Then the crowd divides in two, and both groups run across the plaza, shrieking wildly. Hundreds of spears fly through the air toward a small rolling stone disk.”

The Mysterious Decline Of Cahokia Mounds

Cahokia didn’t last long, but while it did — it thrived. Men hunted, gathered resources, and tended to necessary construction while women worked in the fields and homes, building pottery, mats, and fabrics. There were communal activities and social gatherings, and all were in tune with the natural world they inhabited.

“There was a belief that what went on Earth also went on in the spirit world, and vice versa,” explained James Brown, professor emeritus of archaeology at Northwestern University. “So once you went inside these sacred protocols, everything had to be very precise.”

Ultimately, what was left of the city were several dozen mounds, human remains, and a roster of assorted artifacts. It’s largely unknown why people were killed or no further information regarding the civilization’s disappearance was left behind. There’s no evidence of invasion or warfare that eradicated the entire city.

Wikimedia Commons

A digital illustration of a winter solstice sunrise over Fox Mound from the Woodhenge timber circle circa 1000 C.E.

“At Cahokia the danger is from the people on top; not other people (from other tribes or locations) attacking you,” according to Thomas Emerson.

What then, caused this civilization to cease? Williams Iseminger, an archaeologist and assistant manager at Cahokia Mounds, remains adamant a longstanding threat to the city must have existed for this to occur.

“Perhaps they never were attacked, but the threat was there and the leaders felt they need to expend a tremendous amount of time, labour and material to protect the central ceremonial precinct,” he said.

Despite the theories, the known facts are still insufficient. After a population peak in around 1100, it began to shrink — and then vanish entirely by 1350. Some suggest that natural resources ran out — or maybe political unrest or climate change caused Cahokia’s downfall.

In the end, Cahokia doesn’t even appear in Native American folklore.

“Apparently what happened in Cahokia left a bad taste in people’s minds,” said Emerson.

Wikimedia Commons

St. Louis, Missouri as seen from atop Monks Mound.

All that remains now is a historical site in modern-day St. Louis, which garnered Unesco World Heritage Site status in 1982, and comprises 72 remaining mounds and a museum. It’s visited by around 250,000 people each year. A thousand years after it was built, this site still fascinates those who experience it with their own eyes.

“Cahokia is definitely an underplayed story,” said Brown. “You’d have to go to the valley of Mexico to see anything comparable to this place. It’s a total orphan — a lost city in every sense.”

Src: allthatsinteresting.com