The navel was found with unique imaging technology and is similar to scars living alligators sport

:focal(688x387:689x388)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b3/75/b3759f24-a275-428f-a3dc-b6f2c183ab64/belly-button-close-up.jpg)

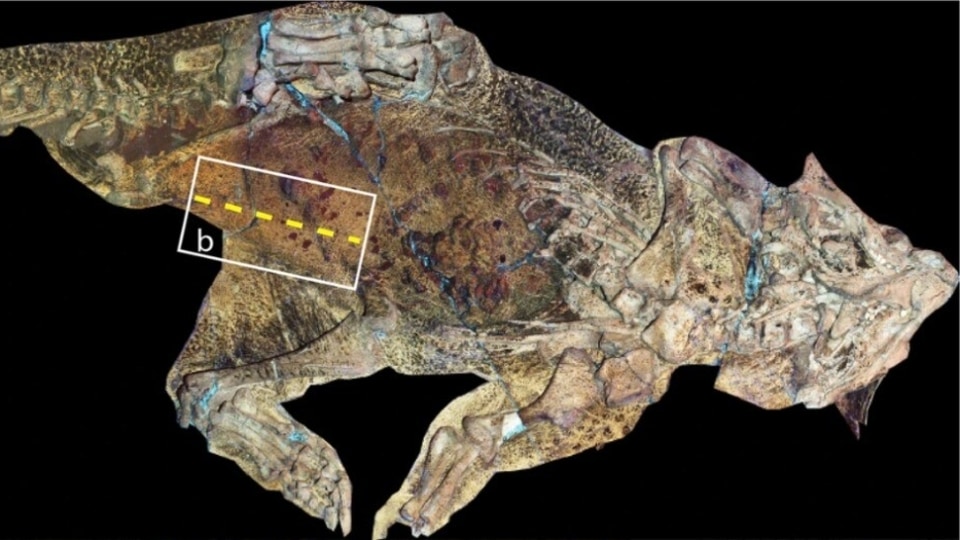

Scientists had long speculated that egg-laying dinosaurs would have an umbilical scar, but this study is the first to find evidence of one. (Pictured: artist representation of a Psittacosaurus and its umbilical scar)

Paleontologists have discovered the oldest belly button known to science. It belongs to a Psittacosaurus, a member of the horned dinosaurs Ceratopsia, in a fossil uncovered in China. The belly button does not come from an umbilical cord, as it does with mammals, but from the yolk sac of the egg-laying creature, reports Science Alert’s Carly Cassella. Details on the find were published this month in BMC Biology.

Modern egg-hatchers like snakes and birds lose their belly button scar within a few days or weeks after hatching. But other organisms keep the “umbilical scar” for the rest of their lives. While inside the egg, the embryo’s abdomen is connected to the yolk sac, which provides the embryo with a food source for growing and developing. The scar appears when the embryo detaches from the yolk sac and other membranes, before or as it hatches from its egg. The scar, known as an umbilical scar, is a non-mammalian belly button, reports Gizmodo’s Jeanne Timmons. The Psittacosaurus umbilical scar is similar to that of an adult alligator and is the first example of one in a non-avian dinosaur that predates the Cenozoic period, 66 million years ago, Science Alert reports.

Psittacosaurus was a bipedal dinosaur that lived during the beginning of the Cretaceous period. Fossils found in Mongolia and China of the horned dinosaur date from 100 million to 122 million years ago. Psittacosaurus measured almost 7 feet long and was noteworthy for its high and narrow skull with a parrot-like beak. Paleontologists have also found on the same Psittacosaurus fossil a dinosaur cloaca and countershading camouflage, Gizmodo reports.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/31/81/3181a5ce-9f0e-4d40-a638-5d10b03a884d/2.jpg)

The team was able to work out the umbilical scar by seeing a change in the pattern of skin and scales where the dinosaurs belly button would be. Bell et al. 2022

Researchers imaged the elusive belly button with Laser-Stimulated Fluorescence (LSF), an imaging technique. They used a modified version of LSF, developed in part by Michael Pittman, a vertebrae paleontologist at the University of Hong Kong and coauthor of the study with Thomas G. Kaye, a paleontologist at Foundation for Scientific Advancement. The modified imaging method increases laser intensity in previously established laser imaging techniques without damaging specimens, allowing fine details to be seen in fossils that otherwise would go unseen, Gizmodo reports.

The Psittacosaurus specimen with the belly button was unearthed in 2002 in China, found lying on its back. Using LSF, the team could analyze each scale, wrinkle and pattern etched on the preserved fossil. “LSF brings out the detail in spectacular fashion,” Phil Bell, a dinosaur paleontologist involved with the study, tells Gizmodo. “It really looks as though the animal could get up and walk away. You can see every little wrinkle and bump in the skin. It looks so fresh. Imagining these animals as living, breathing entities, rather than just dead skeletons, is what fascinates me. Bringing them to life is one of the major goals of my work.”

The team was able to image the umbilical scar, which had faded over time, by seeing a change in the pattern of skin and scales where the dino’s belly button would be. They also determined that the scar was not from a healed injury because the umbilical scales were smooth and arranged along the midline of the dinosaur. If the scar were an injury, it would have displayed regenerative tissue that could cut through and be inconsistent with the scale pattern. To determine the age of the fossil, the team measured the length and growth of its femur and found that the specimen was nearing sexual maturity at six to seven years old, per Gizmodo.

Scientists had long speculated that egg-laying dinosaurs would have an umbilical scar, but this study is the first to find evidence of one, Science Alert reports. The researchers note that while a scar was found in this specimen, it may not have been present in all non-avian dinosaurs.

Source: smithsonianmag.com