A previously unknown species of great ape that was well adapted to both walking upright as well as using all four limbs while climbing has been identified from fossils found in southern Germany.

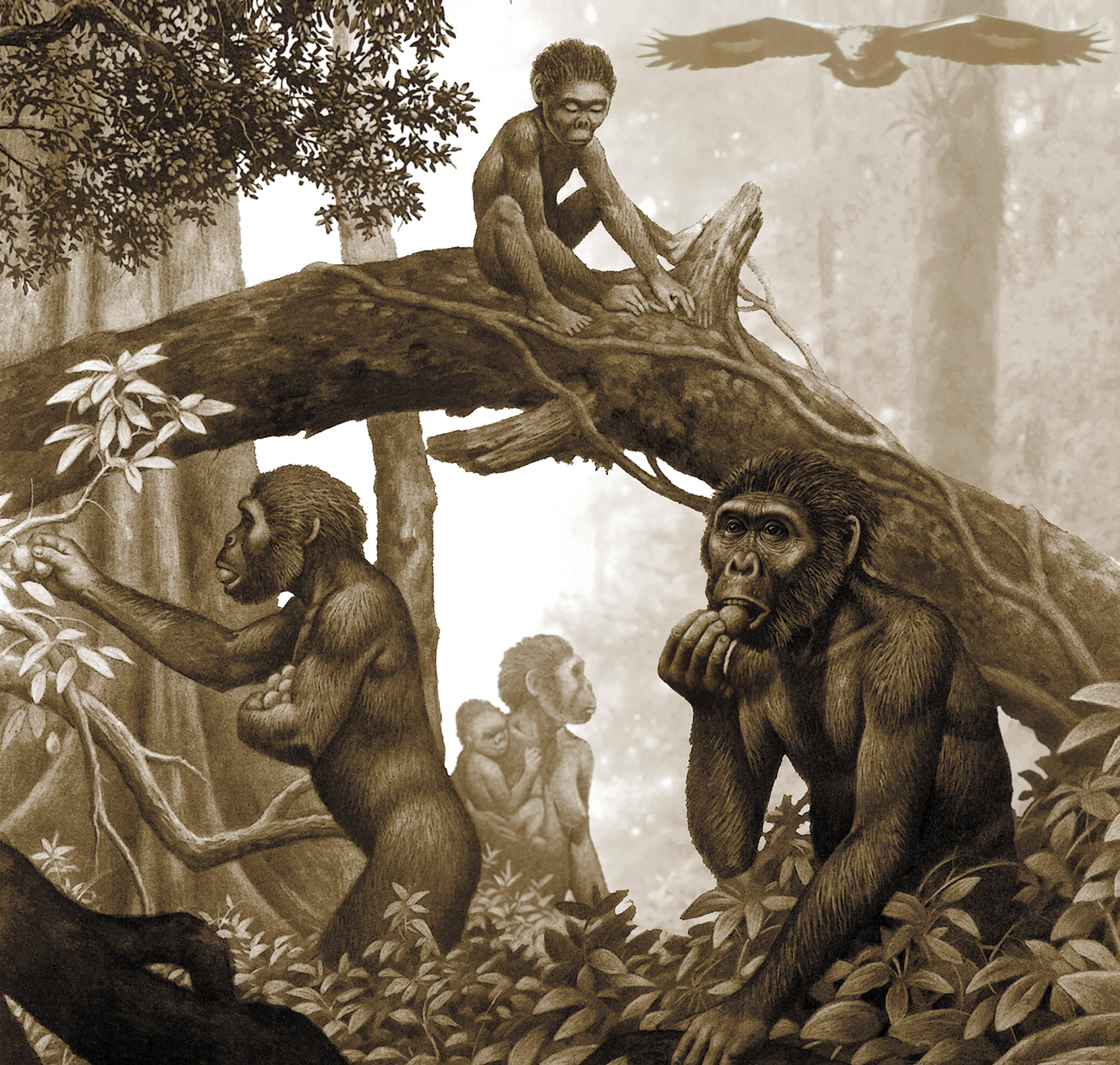

Danuvius guggenmosi, a great ape that lived some 12 million years ago (Miocene period) in what is now Germany. Image credit: Velizar Simeonovski.

Named Danuvius guggenmosi, the ancient great ape lived during the Miocene period, 11.62 million years ago.

The primate was about 3.3 feet (1 m) in height. Females weighed about 18 kg, less than any great ape alive today, males had a mass of about 31 kg, also at the low extreme of modern great ape body size.

The fossilized remains from at least four individuals of Danuvius guggenmosi (a male, two females and a juvenile) were unearthed in the Hammerschmiede clay pit in the Allgäu region of Bavaria between 2015 and 2018.

The most complete skeleton belonged to a male and had body proportions similar to modern-day bonobos.

Thanks to completely preserved limb bones, vertebra, finger and toe bones, Professor Madelaine Böhme from the Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen and colleagues were able to reconstruct the way Danuvius guggenmosi moved about in its environment.

“For the first time, we were able to investigate several functionally important joints, including the elbow, hip, knee and ankle, in a single fossil skeleton of this age,” Professor Böhme said.

“It was astonishing for us to realize how similar certain bones are to humans, as opposed to great apes.”

The bones from the skeleton of a male Danuvius guggenmosi. Image credit: Christoph Jäckle.

The team’s findings indicate that Danuvius guggenmosi could walk on two legs and could also climb like an ape.

The spine, with its S-shaped curve, held the body upright when standing on two legs. The animal’s build, posture, and the ways in which it moved are unique among primates.

“Danuvius guggenmosi combines the hindlimb-dominated bipedality of humans with the forelimb-dominated climbing typical of living apes,” said Professor David Begun, a researcher at the University of Toronto.

“These results suggest that human bipedality evolved in arboreal context over 12 million years ago.”

“In contrast to later hominins, Danuvius guggenmosi had a powerful, opposable big toe, which enabled it to grasp large and small branches securely,” said Professor Nikolai Spassov, from the Bulgarian Academy of Science.

“The ribcage was broad and flat, and the lower back was elongated; this helped to position the center of gravity over extended hips, knees and flat feet, as in bipeds.”

The results are supported by a recent study of the hip-bone from the 10 million-year-old ape Rudapithecus hungaricus found in Hungary.

“That fossil also indicates that the European ancestors of African apes and humans differed from living gorillas and chimpanzees,” Professor Begun said.

Source: sci.news