Artificial intelligence has now officially seeped into ancient history. Linguists at the Institute for Assyriology at Ludwig Maximilian University in Germany have created an artificial intelligence (AI) bot to help piece together and decode illegible fragments of ancient Babylonian texts. It’s been dubbed “the Fragmentarium.”

No longer are the linguistic services of algorithms and machine learning bots the reserves of global marketing elites. Unless you’ve been asleep these last few weeks you will know that 2023 has already marked the beginning of what will be remembered by our children as the first steps in an artificial intelligence revolution.

Perhaps the most well known new language-based AI bot is ChatGPT. Based on OpenAI, this online tool now provides writers with the ability to reword, restructure and enhance written work, as if they had researched and written the articles themselves.

Directing AI at Ancient Texts – The Fragmentarium

At the other end of the AI scale, in the halls of academia, a new artificial intelligence bot has been developed that will soon offer armchair archaeologists the ability to piece together ancient texts. Professor Enrique Jiménez, at the Ludwig Maximilian University (LMU) Institute of Assyriology in Munich, Germany, leads a team of linguists from the Iraq Museum and the British Museum .

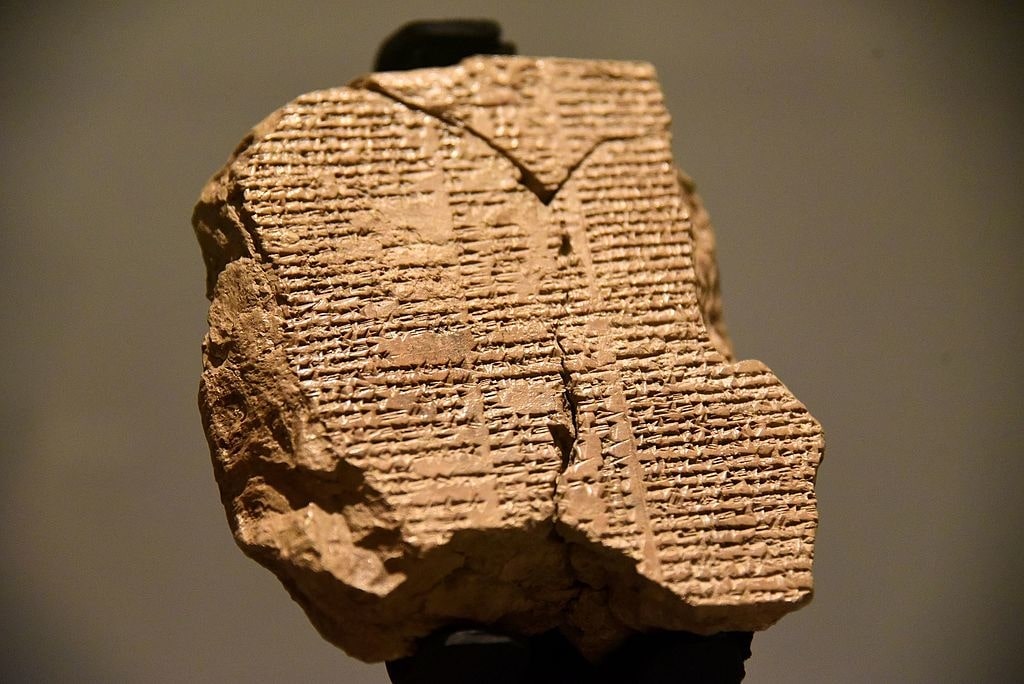

Since 2018, they have not only digitized “every surviving Babylonian cuneiform tablet ,” but they have now photographed and processed around 22,000 fragments of ancient text . To help piece these fragments together the team has created a unique AI database called the “Fragmentarium.”

Functioning on both systematic and automated methods, this new AI program has already identified hundreds of new manuscripts. Furthermore, it matches up old text fragments, including pieces from the most recent tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh which is considered the first work of literature in the world.

Written in the year 130 BC, this ancient Mesopotamian odyssey is recorded in the Akkadian language and recounts the adventures of Gilgamesh, a king of the Mesopotamian city-state Uruk (Iraq). The researchers said this newly discovered version of the ancient Epic is “significantly younger” than the oldest known version of the epic which was written in cuneiform characters on clay tablets over 4,000 years ago.

Fragmentarium AI Is Going Public

In an article published on PHYS, Dr. Jiménez said that his new research, and the AI tool, has “the potential to greatly enhance” the understanding of Babylonian literature and culture. But these new insights will not be the exclusive preserve of academics. For the Fragmentarium AI tool will be made public later this month, along with a digital version of the Epic of Gilgamesh that will contain all of the known transcriptions of cuneiform fragments that have been identified to date.

However, only two-thirds of this ancient text has been restored so far, and Jiménez said there are “thousands of fragments that have not yet been identified.” Nevertheless, from now on everybody, including you, will be able to use Fragmentarium to explore and study the fragments that have not yet been identified.

Therefore, Fragmentarium will rely on the power of crowd-sourced efforts, somewhat like a big online jigsaw with thousands of conceptual hands stitching together broken old texts. Learning as it goes, the artificially intelligent Fragmentarium is expected to play a major role in the ongoing job of reconstructing ancient Babylonian literature.

Timeless Relevance of Ancient Texts Revealed by Fragmentarium AI

The work of Jiménez and his team has also led to the discovery of previously unknown genres in Babylonian literature, such as hymns dedicated to the city of Babylon. They have, for example, identified 15 fragments of a hymn that speaks of the arrival of spring in Babylon and how the warmer weather affected the city. It was discovered that this particular hymn was important in the education of Babylonian children, as the team of researchers found that schoolchildren copied it out in lessons.

As his understanding of ancient Babylonian language and culture increases, Jiménez said he is inspired by “the beauty and timeless relevance of the texts.” In particular, he is enchanted by the sorts of questions that Babylonians asked themselves, such as the question of mortality. Dr. Jiménez says the question of “how we should live when we know we must die,” is posed in the Gilgamesh epic.

The Babylonian’s answer to this deeply esoteric question: “how we should live when we know we must die,” is currently lost. But with Fragmentarium at work in the public domain, it is hoped that the answers to these kinds of questions, as they appeared in Babylonian literature and culture, will soon be revealed thanks to the use of artificial intelligence.