A Scientist Claims The World’s Oldest Pyramid Is Hidden in an Indonesian Mountain

When Dutch colonists became the first Europeans to discover Gunung (Mount) Padang in the early 20th century, they must have been awestruck by the sheer scale of their ancient stone surroundings.

Here, scattered across a vast hilltop in the West Java province of Indonesia, lay the remnants of a massive complex of rocky structures and monuments – an archaeological wonder since described as the largest megalithic site in all of Southeastern Asia.

But those early settlers couldn’t have guessed the greatest wonder of all might lay hidden, buried deep in the ground below their feet.

A Shocking Discovery At Gunung Padang

Located in the West Java Province of Indonesia, Gunung Padang doesn’t look like a pyramid. It looks like a large hill covered in broken columns of ancient volcanic rock, a kind of prehistoric graveyard where all the tombstones have been knocked down.

For many years, that’s all archeologists thought the site was. The Dutch colonizers who came across it in 1914 identified it as an ancient megalithic site, the remains of some stone monument prehistoric peoples had cobbled together on raised ground for a purpose lost to time.

While it was the largest megalithic site in Indonesia, it wasn’t nearly as significant as those in other places, and its stones weren’t the oldest; they were dated to around 2,500 years ago. Interest in the site was limited — that is, until 2010, when Danny Hilman Natawidjaja arrived on the scene.

Hilman, a researcher from the Indonesian Institute of Sciences, thought there was more to the site than anyone suspected — and he was going to prove it. He would later tell LiveScience, “It’s not like the surrounding topography, which is very much eroded. This looks very young. It looked artificial to us.”

Using careful excavations and remote sensing techniques like ground-penetrating radar and seismic tomography, he and his team got to work.

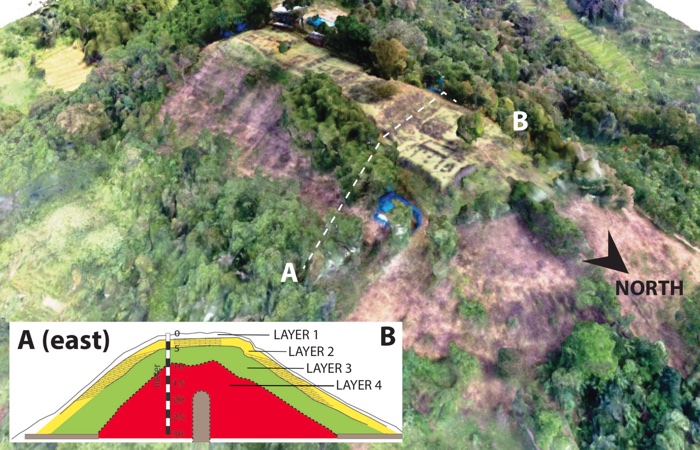

What they found stunned the archeological community. The majority of the 100-meter hill is man-made — and it’s not actually a hill at all. It’s a terraced pyramid, built up over millennia by the oldest civilizations the world has yet discovered.

Pulling Back The Layers Of The World’s Oldest Pyramid

The structure under the hill appears to be massive: researchers estimate that it’s as much as three times larger than Java’s famous Borobudur Temple Compounds. But what purpose it served and whether there’s a tomb at its heart remain a mystery. Gunung Padang doesn’t give up its secrets easily.

The enigma is largely a result of the pyramid’s complexity: the site was inhabited and reworked multiple times, as evidenced by its distinctive layers.

The level just below the hill’s grassy modern surface appears to have been constructed by a society that occupied the region around 600 BCE. But they weren’t the first on the scene — not even close.

That society was simply papering over the work of another civilization, this one dating back to 4,700 BCE. Their work is buried some four or five meters below the surface.

And yet this group, too, was building off what their forebears had already done. Digging deeper into the hill reveals an entirely new layer, this one roughly 10 meters below the surface, that dates back to around 10,000 BCE.

The heart of the pyramid, the deepest layer, appears to have been constructed over millennia, with the oldest bits hailing from as far back as 25,000 BCE.

If the carbon dating on this deepest section is correct, then Gunung Padang didn’t just beat the pyramids — it clocks in ahead of the first recognized civilization in Mesopotamia. It shows evidence of a settled society 12,000 years before the agricultural revolution.

The society that first built at the site of Gunung Padang even predates the last Ice Age, which ended in 11,500 BCE — a date that archaeologists have traditionally used to mark the beginning of the great human civilizations.

Nationalism And Skeptics Play Politics With Gunung Padang

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the discovery has been controversial. The nature of the find alone makes the stakes enormously high: Indonesia may be home to the earliest advanced civilization the world has ever uncovered. The find is a source of enormous pride to the Indonesian people and especially the government, which has spared no expense on the excavation.

Yet some suggest this enthusiasm has led Hilman and his team to come up with biased interpretations of the evidence they’ve uncovered. The team’s carbon dating procedures have fallen under scrutiny, and some believe the results don’t mean what the researchers claim they do.

Also raising eyebrows are the remains of what researchers believe was an ancient cement mixture used to glue Gunung Padang’s stones together. Its composition, a combination of clay, iron, and silica, suggests that iron-melting technology was in use well before the beginning of the Iron Age, drawing a picture of a society far more advanced than any other known to have existed at the time.

Several scientists, however, have spoken out against this conclusion, saying that the mortar isn’t necessarily man-made; similar compositions are found in nature. Vulcanologist Sutikno Bronto doesn’t even believe the structure is a pyramid: he thinks it’s the neck of a volcano near the site.

As this view of Mount Bromo illustrates, Java is a land of volcanoes — which has led some to suspect that the pyramid of Gunung Padang is really just the neck of one of the region’s many volcanoes.

There’s also the fact that nearby excavations haven’t turned up similar results. Less than 30 miles away, ancient bone tools dating back to 7,000 BCE were discovered in a cave. For some, it’s hard to believe that the builders of Gunung Padang could have been advanced enough to build pyramids while their closest neighbors were still carving tools from the bone.

Proponents of Hilman’s conclusions have suggested the answers might lie beneath the waves of the Java Sea. Millennia ago, when sea levels were lower, the ocean bed was land — and perhaps the home of the great society the research team envisions. But the sea has since swallowed the evidence of their existence, making concrete proof difficult to find.

In short, though Hilman and his researchers have put forward a compelling challenge to those who believe the prehistoric peoples of 20,000 years ago were simple hunter-gatherers, many remain unconvinced. The hunt for evidence continues, and the debate rages on.