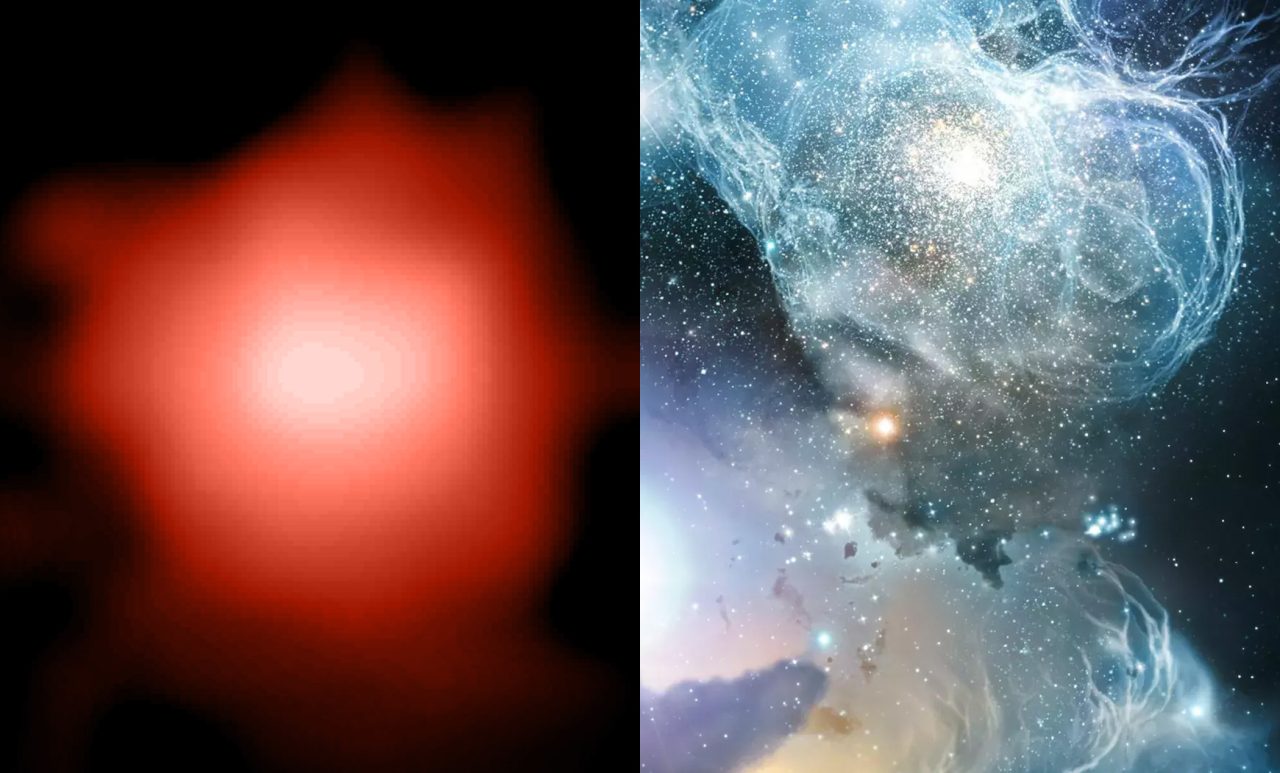

Spacecraft have explored both the nearside (left) and farside of the Moon. Humans, however, have landed only on the nearside — the half that always remains visible from Earth — due to communication requirements. NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

Why do we see only one side of the Moon from Earth? Have humans explored the other side, and, if so, is it different from the nearside?

—Sara O’ConnorGresham, Oregon

Earth orbits the Sun once every 365 days (a year) and spins on its axis once every 24 hours (a day). The Moon orbits Earth once every 27.3 days and spins on its axis once every 27.3 days. This means that although the Moon is rotating, it always keeps one face toward us. Known as “synchronous rotation,” this is why we only ever see the Moon’s nearside from Earth.

All of the manned space missions to the Moon have landed on the nearside due to communication needs, so humans have physically explored this side much more.

We have remotely explored both sides of the Moon with orbiting satellites. In 1959, the Soviet Luna 3 first photographed the farside, and in 1968, as NASA’s Apollo 8 orbited the Moon, human eyes first viewed it. Since then, many satellites have sent back pictures and other data showing that the farside of the Moon differs from the nearside. (On Jan. 3, 2019, China’s Chang’e 4 lander became the first lunar lander to touch down on the Moon’s farside.)

The nearside is darker than the farside (which is ironic, as a nickname for the farside is “the dark side of the Moon” even though it’s actually the brighter side of our satellite). Mare deposits of dark basalt fill many large basins on the nearside, whereas the highlands of the farside are made from a light-colored mineral called feldspar. This may result from even another difference: The lunar crust is thinner on the nearside, which means that the mantle (the once molten, denser layer that underlies the crust) is closer to the surface there. Asteroid impacts could more easily fracture the crust down to the level of the mantle on the nearside, allowing magma to rise up to fill impact basins and form mare deposits.